Rail Transport Issues

FUEL FOR URBAN DESIGN

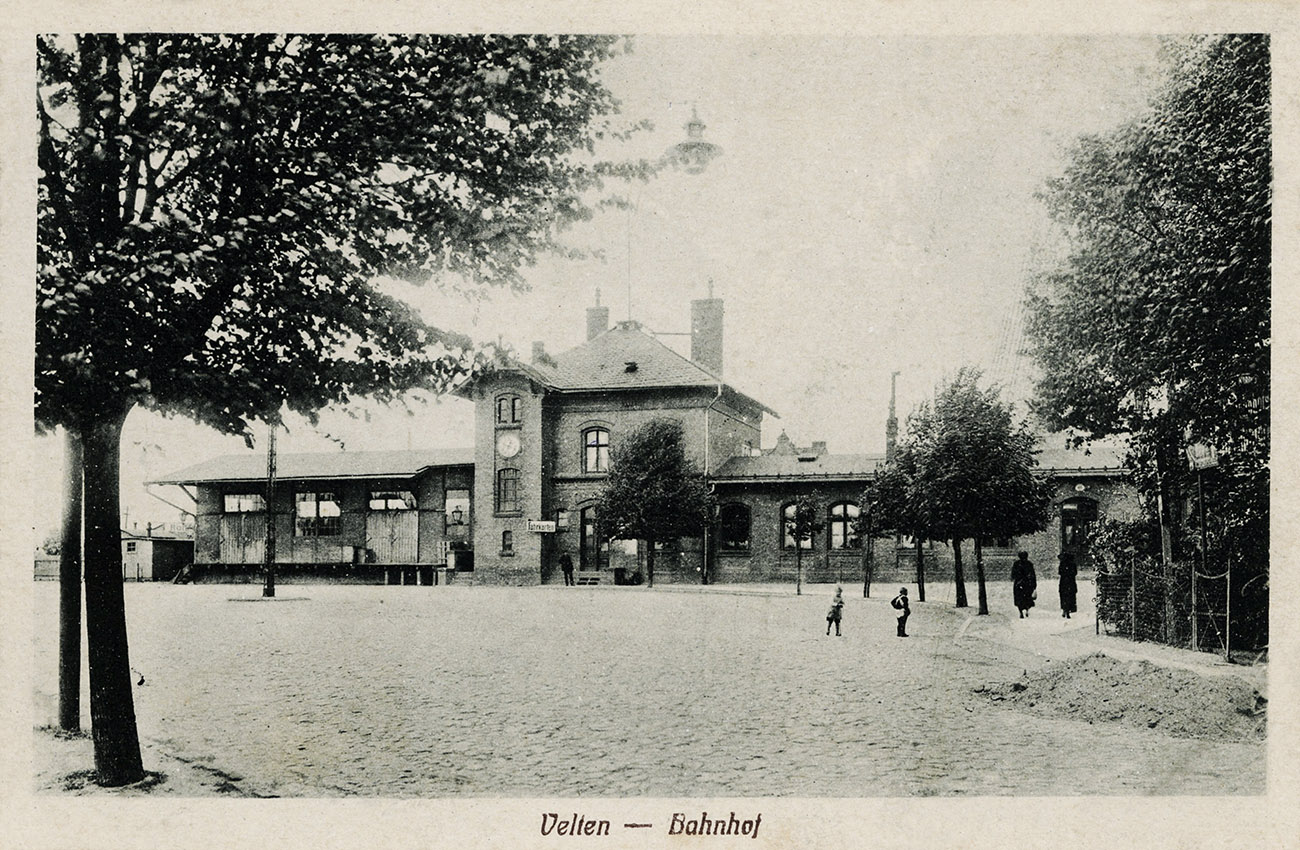

Train stations have provided structure to the greater Berlin area since long before Greater Berlin was established. They were the most important engines of urban development in the imperial era. They created new places in the city: the squares in front of stations, station roads, and the areas behind stations. However, there was no central train station before 1920, just a ring of several terminus train stations surrounding the city centre. Today, the new central train station is the destination for long-distance rail transport arriving to the entire city. Its opening in 2006 gave rise to the construction of a whole new district in an area that was on the periphery when the city was divided.

Photo Philipp Meuser, 2020

The greater Berlin area came about as a result of the railway. High-speed rail transport made it possible to build the suburbs. The formation of Greater Berlin led to fundamental reform of the public transport system. A single, unified municipal transport company was created in 1928: Berliner Verkehrs-AG (BVG). The reforms affected buses and the U-Bahn, but they were primarily focused on trams, which were the most important means of transport in the city at that time. Following the Second World War, the local public transport network was largely separated. Trams in West Berlin closed, but the underground U-Bahn network was expanded on both sides of the wall. An outer railway ring was built in order to bypass West Berlin. After reunification, a new system of train stations was created, thereby reducing the importance of the divided city’s two central train stations: Zoologischer Garten and Ost-Bahnhof. At the same time, the project of the century was finally carried out: the north–south main rail line.

Gustav Böß, mayor of Greater Berlin from 1921 to 1929 Berlin Today: City Administration and the Economy

Berlin is the most important European rail hub for freight and passenger traffic.

Berlin’s tremendous development is thanks in part to the insight and drive of the former Prussian rail authorities and current German National Railway authorities.

The facilities at Berlin’s train stations and station forecourts are outdated. A continuous north–south main line (must be created).

Merging the city’s urban transport companies and standardising the fare system gained widespread recognition among both the general public and experts. The Berlin example served as a model for others.

One of the most important tasks of the Berlin city administration is to expand the high-speed rail network as quickly as possible.

Gustav Böß,

mayor of Greater Berlin from 1921 to 1929

Berlin Today, Berlin 1929

Pedestal from the Elevated Railway

Three-roller load-bearing pedestal from the elevated railway line at Schlesisches Tor, 2020. The double decoupling of guideways and the supporting construction continues to protect the elevated line from material fatigue.

Greater Berlin: A Child of the Rails

Even in the years before the First World War, Berlin needed an extensive high-speed rail system in order to transform the city centre and ensure the swift growth of the greater Berlin area. The two ‘station streets’ (Leipziger Strasse and Friedrichstrasse), which carried passengers from key train stations to the city centre, became the most important main streets in the city centre. The high-speed rail system also enabled the rapid rise of the centre of the New West area at the Zoologischer Garten station as well as the expansion of the villa colonies in southwest Berlin and elsewhere. It also promoted further migration of industry to the outskirts of the city. The Prussian Railway Division orchestrated the rail-guided expansion of Berlin, in particular from the 1880s onwards. The radial rail network led to a star-shaped settlement pattern, and this relatively sustainable basic city pattern is still tangible today.

The Network of the Circular Railway, Light Railway System and Commuter Lines

A map of commuter lines in 1920. All of the lines end outside the boundary of Greater Berlin. Around half of the lines were single-track, and some were also long-distance lines.

Diagram of the Expansion into the Suburban Area

A dynamic model of radial urban expansion developed in 1911. Richard Petersen’s star-shaped settlement pattern shows the desired form of modern urban development: Growth takes place along the lines radiating out from the centre, with commuter train lines providing the supporting framework. The growth corridor condenses at the train stations. Building density reduces as you move outwards from the central core. Open spaces stretch between the lines radiating out from the centre, reaching all the way into the central core. Petersen was a transport planner and, together with Rudolf Eberstadt and Bruno Möhring, won third prize in the Greater Berlin Competition (1908–1910) with the radial urban expansion model.

The Long Search for a Central Train Station

Berlin’s lack of a central train station was seen as a serious failure even during the Greater Berlin Competition (1908–1910). Numerous competition entries proposed having two central train stations, which would be connected by an underground line running from north to south. Lehrter train station was selected as a suitable location for the north station, while the Deutsches Technikmuseum (German Museum of Technology) would be the site for the south station. The plans for a proper central train station at the site of the former Lehrter station were set out in considerable detail during the Weimar Republic. Nazi-era planners then moved the site of the northern central station further north towards Gesundbrunnen. When the city was divided, Lehrter station lost its significance due to its position on the periphery of both East and West Berlin. The new central station opened here in 2006 – after around 100 years of planning.

Proposals Submitted for the Greater Berlin Competition

Berlin Mitte Archive, no. AK-6952

Proposals During the Weimar Republik

Bruno Möhring, ‘The Advantages of Tower Blocks’, lecture held at the Prussian Academy of Civil Engineering, 22 December 1920 (Berlin, 1920), p. 5, fig. 4

The Plan for Two New Large Train Stations during the Nazi Era

Photo Wolfgang Schäche collection, Berlin

Central Train Stations in the Divided City: East Berlin

IRS (Erkner) / Scientific Collection, no. D1_1_3_2A-005

BVG: A Child of Greater Berlin

A city having a single, central transport company that uses a standardised fare system is not something that should be taken for granted, as it’s not always a given. It wasn’t until after Greater Berlin was established that it was possible to get past the situation of having several competing private and public transport companies. The crowning achievement of all of this was the introduction of a fixed fare of 20 pfennigs in 1927. This fare also allowed for passengers to change to another line. Berlin’s public transport company, Berliner Verkehrs-Aktiengesellschaft (BVG), was founded in 1928 and was the largest transport company in the world at the time. City Councillor for Transport Ernst Reuter spearheaded the foundation of the company.

The Tram and U-Bahn Network

Berlin, Berlin: An Exhibition on the History of the City (Berlin, 1987), pp. 474 / 475

The rail network was further expanded after Greater Berlin was established. Trams made up 50 per cent of the total public transport system in 1928, while elevated and underground lines made up 15 per cent. In the years after 1945, trams were considered old-fashioned in West Berlin and the system was closed down.

BVG Company Housing Complexes

40 Years of the Berlinische Boden-Gesellschaft (Berlin, 1930), after p. 132

Combining tram depots with housing for tram employees was an approach unique to Greater Berlin. The residential buildings were built by a company-owned housing association: the non-profit Heimstättenbau. Jean Krämer was the outstanding architect of these complexes. He has largely been forgotten today.

After 1990: A Rail Renaissance

Berlin’s rail system was reorganised following German reunification. A new structure was developed, discussed and agreed on and ultimately implemented within a very short space of time. The Federal Ministry of Transport opted for the mushroom model, and this has provided structure to Berlin since its adoption in 1992. It would now fulfil two dreams: determining a central train station on the exact site that was proposed one hundred years ago and developing the underground, long-distance North–South main line, which brought with it another key new major train station: Südkreuz. Work is also underway to expand the tram system and in particular, to reintroduce trams to the western part of the city. That’s not all. The city is growing and local and regional transport must be rapidly expanded, yet the necessary shift towards sustainable transport must be considered. The first plans are in place as part of the i2030 transport project.

Breathtakingly Fast: The Railway Mushroom Model

Deutsche Bahn AG

After reunification, it was by no means clear how the unified rail system should be reorganised. Discussions focused around two models: the mushroom model and the ring model.

Initially Almost Overlooked: The New Südkreuz Station

Photo Philipp Meuser

Südkreuz station went almost unnoticed as it quietly developed in a hidden location. The urban development opportunities that a key train station like this presents were also overlooked for a long time.

The Outer Railway Ring: A Forgotten Treasure?

Photo Schubert; DBAG Historical Collection

It was well known to East Berliners, but not so much to West Berliners: The outer railway ring connects the radial routes of the suburban transport system. It was initially scaled back after reunification. Its potential was yet to be discovered.

Photo Harald Bodenschatz

Expansion of the Tram Network

Holger Orb / Tilo Schütz, Trams for all of Berlin (Berlin, 2000), insert

The revival of the tram is an unmistakable reality. Not only are we seeing a push to bring back trams to the western part of the city, plans are also in place to massively expand the tram network. However, it is not yet clear how trams will be integrated into the public space in a way that’s compatible with the city.

Big Plans:

i2030

i2030 project

The i2030 project involves the states of Berlin and Brandenburg working with Deutsche Bahn and the Berlin-Brandenburg Transport Association to plan multiple sub-projects focused on adapting infrastructure to increased requirements in the coming years. In future, it will be necessary to consider whether the outer railway ring – constructed by the German Democratic Republic to detour around West Berlin – can still play a key role.