We Are Not Alone! – Perspectives from Europe

Moscow, Vienna, Paris, London

Around 1900, attempts began in Europe to reorganise large and rapidly expanding urban areas, politically, administratively and in terms of planning. This was an extremely difficult process, and not just in Berlin, where efforts were hindered by conflicting interests and so rarely successful.

There are four main periods during which these attempts were pronounced. One: before the First World War, when metropolitan regions became a reality on a larger scale for the first time in history. Two: in the 1930s and during the Second World War, when democracies embarked on large-scale concepts under difficult conditions and hegemonic dictatorships set their sights on massive growth in their capitals. Three: in the 1960s, when suburbanisation was in full swing. And four: today, at a time when large, growing cities have to look towards a sustainable future. Here, four European capitals are of particular interest: Moscow, Vienna, Paris and London. All have been involved in the administrative development and urban planning of metropolitan regions for more than 100 years and are still wrestling with such issues today. In the following pages, there is an overview of the history, programmes and practice of urban planning in their metropolitan areas.

While Greater Vienna and Bol’šaja Moskva, like Greater Berlin, are unified municipalities, Grand Paris has remained an unrealised administrative project to this day. Greater London is not a unified municipality, but a regional association of 32 boroughs and the City of London, each of which of has limited powers as it is under the leadership of the Greater London Authority.

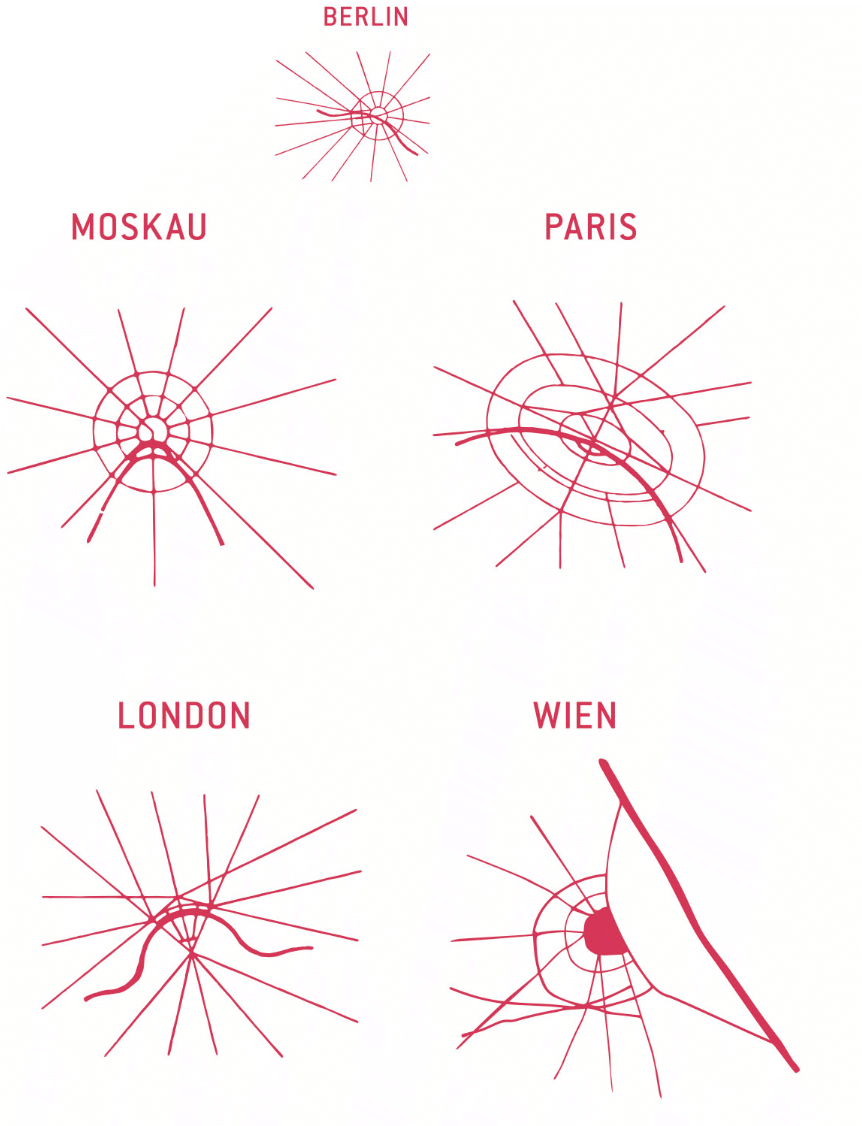

published in 1938 in the grand photobook Moskva

Rekonstruiruetsya (Moscow under Reconstruction). The authors of the 1938 versions were likely Aleksandr M. Rodčenko and Varvara F. Stepanova. However, the diagrams can be traced back to Eugène Hénard’s sketches, which he had published in Études sur les transformations de Paris (1903–1906), although there is no mention of this in the Soviet publication. They were then also printed in 1909 in Daniel H. Burnham and Edward H. Bennet’s book The Plan of Chicago and in 1911 in Werner Hegemann’s volume Der Städtebau nach den Ergebnissen der allgemeinen Städtebau-Ausstellung in Berlin nebst einem Anhang: Die Internationale Städtebau-Ausstellung in Düsseldorf 1910 – 1912 – a sign of the high esteem in which these sketches were held, as well as of the international networking within the discipline of urban planning.

The diagram of Vienna was redesigned based on

historical sketches by Lilja Schick.

Bol’šaja Moskva (Greater Moscow)

Capital Region between Europe and Eurasia

Moscow is a city with wide vistas and long thoroughfares, but it’s rarely possible to make out the city’s historical structure. It looks very different on the map: There are five concentric rings around the centre, where the Kremlin is located, and they look almost like a matryoshka nesting doll cut in half horizontally. The innermost ring circumvents the Kremlin. Travelling in a clockwise direction, it goes through the Kitay Gorod neighbourhood in the historic quarter, past Zaryadye Park and along the high Kremlin walls that face the Moskva River. The Boulevard Ring is incomplete in the south, as it forms a semicircle from one river embankment to another, and it is crossed by a boulevard in the middle. The officially designated Third Ring was only completed in the 2000s and runs roughly parallel to the 54-kilometre-long Moscow Central Circle, which served as the border of the city until 1960 as the Moscow Little Ring Railway. Further out, the Moscow Automobile Ring Road (Moskovskaya Koltsevaya Avtomobilnaya Doroga or MKAD) dates from the early 1960s and encircles the city. It is over 100 kilometres in length. From here you can see how densely built up Moscow is. Tower blocks and monumental prefabricated suburbs fill the horizon. The Kremlin forms the core of this oversized matryoshka doll. It is symbolic of the lighter and darker sides of Russia: Joseph Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev – still considered heros by some – led the Soviet people for seven decades from inside its historic walls; now it is an attraction for legions of tourists with cameras in hand trying to capture the magnificence of old and new Russia.

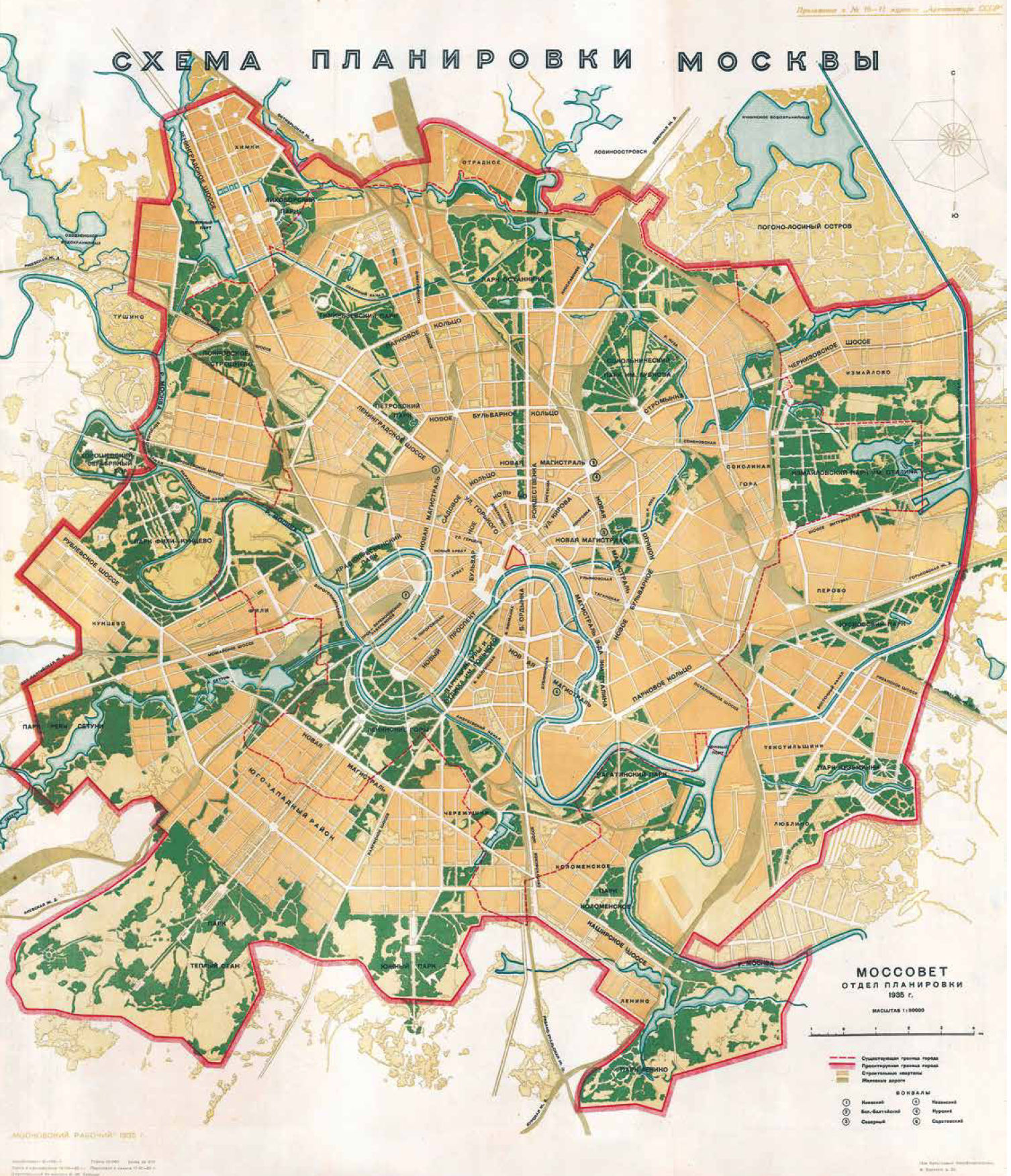

General Plan for a City of Millions:

Moscow from 1935 to 1941

The second Five-Year Plan saw Joseph Stalin fundamentally change the approach to urban development and housing priorities from 1933 onwards. Building new industrial cities fell by the wayside in favour of expanding Moscow as the capital of the Soviet Union and the global communist movement. The General Plan of Moscow adopted in 1935 reflects this development. It was geared towards tremendous urban growth. The metropolitan area grew from 28,500 to 60,000 hectares. The southwest of the city was identified as the most important development area for housing construction. The vast new city was to be surrounded by a green belt made up of forest parks. The opening of the first metro line in 1935 was one of the highlights of the city’s urban redevelopment.

the next 10 years.

Arxitektura SSSR 10–11 (1935)

Housing Construction and the Olympic Games as Engines of Development:

Moscow from 1955 to 1985

Standard Projects and Industrial Prefabrication

Schusev State Museum for Architecture, Moskau

The death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 prompted a wave of migration that put pressure on Moscow’s housing shortage. Nikita Khrushchev recognised housing construction as a key policy issue and eventually prevailed in the power struggle to become Stalin’s successor. For Moscow, this meant large-scale expansion of microdistricts to the outer Moscow Automobile Ring Road (MKAD).

In addition to the icons of Soviet modernism, the construction programmes under Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev were aimed at the masses. Moscow became a testing ground for what was later to be implemented throughout the USSR. Under Khrushchev, architects and engineers experimented with industrial prefabrication, while under Brezhnev, building programmes expanded from manageable residential districts to microdistrict complexes for 150,000 residents, the size of which corresponded

to a city of its own. Housing construction was the real engine of urban development during both periods. Preparations for the 1980 Olympic Games came to the fore in the late 1960s. For Moscow, the large Olympic buildings brought about a push to modernise previously neglected neighbourhoods and led to improvements in transport infrastructure and urban services technology.

Greater Vienna

Ugly and Bland?

Now The Most Livable City In The World

For The Tenth Time

Vienna and Berlin: The two cities are polar opposites. Vienna was once the venerable capital of the Holy Roman Empire, while Berlin is the rustic upstart. When the German Empire was founded under Prussian leadership, Vienna’s loss of importance was inevitable. The incorporation of the suburbs in 1892, the regulation of the Danube and construction of the railway in the countries of the dual monarchy all contributed to creating the conditions for rapid industrialisation. Yet Berlin’s economy developed faster. However, the formation of Greater Vienna in 1892 became a model for Greater Berlin. Following the First World War, social housing, municipal infrastructure and local amenities were placed on a democratic and public service foundation in Vienna. The city lost its independence and became a federal city with the establishment of the Austro-fascist state in 1934. Between the annexation of Austria to the German Reich in 1938 and the beginning of the Second World War in 1939, monumental plans were developed for Vienna based on the model of Berlin, and an even larger Greater Vienna was formed in 1938. After 1945, Vienna, like Berlin, was divided into four occupation zones under the control of the Allies, and Greater Vienna was reduced in size again in 1954. The Allies left Vienna in 1955, accelerating the city’s car-oriented, suburban conversion and expansion. Later, the fall of the Iron Curtain brought economic benefits. The new city government has been strengthening the city’s institutions again since 2010. The city’s municipal housing and land policies in particular remain much-discussed – like in Berlin

Red Vienna (1919 – 1934)

After the First World War, Austria declared itself a republic and expelled the Emperor. Cooperative and municipal institutions were created for all areas of daily life. Vienna soon became a testing ground for Austro-Marxist reforms and changes. The municipal housing construction of the housing tax era – with its monumental block structures with swimming pools, educational institutions, consumer cooperatives and the urban infrastructure – is evidence of this era. The Red Vienna experiment came to a bloody end with the Dollfuß putsch, the violent accession of power by the clerical state in February 1934.

Black Vienna (1934 – 1938)

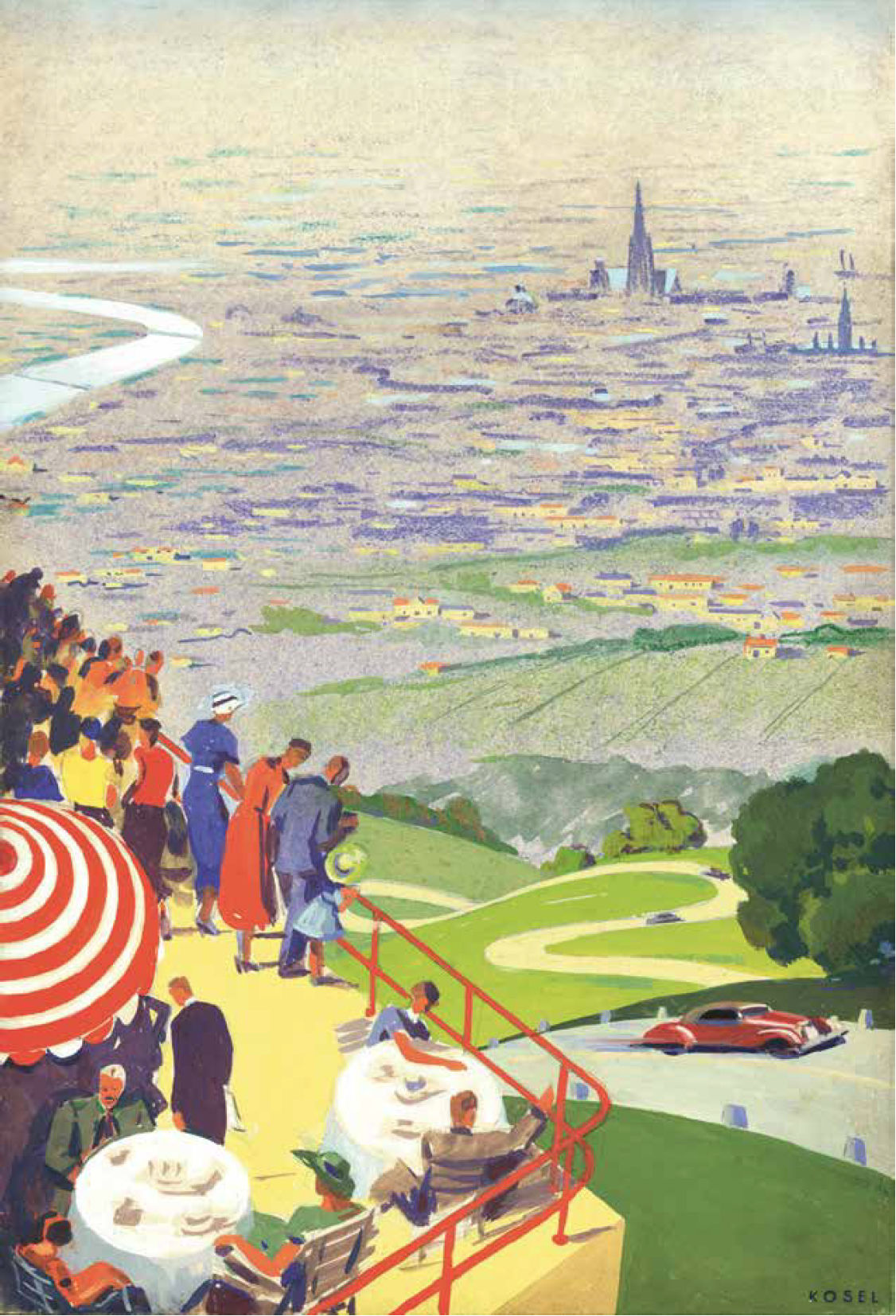

Hermann Kosel, Wien Museum, no. 58201/5/2

Urban development during the Austrofascism period focused on job creation through projects such as the Höhenstrasse scenic road and the Reichsbrücke bridge, small-scale housing developments, churches and exclusively private urban regeneration projects. During this period, the RAVAG broadcasting centre and the small Freihausviertel area on Operngasse were developed, but other projects did not get off the ground, including the Führerschule at Fasangarten, the central train station and airport, and the Dollfuß monument. The architecture was dominated by classic modernism and acted as a rationalist counterpoint to the castle-like look of the superblocks built during the Red Vienna era.

Grand Paris

An Unfulfilled Promise

Paris could already look back on a long history at the beginning of the twentieth century. France’s capital has been the subject of urban improvement projects since the Middle Ages. The major urban redevelopment programme managed by Prefect of the Seine Georges-Eugène Haussmann between 1853 and 1870 transformed Paris into a city committed to capitalism and modernity and made it a model for all of Europe. However, all of these plans focused on the area within the city walls. Comprehensive plans had not been made for Paris in the same way as those developed for cities like Vienna and Munich and their metropolitan areas at the end of the nineteenth century. Grand Paris only came onto the agenda at the beginning of the twentieth century. The various plans for the city region that have emerged since then testify to a rich and self-centred Paris alongside poorly equipped city suburbs. Paris intramuros developed differently from the surrounding metropolitan area, with the state playing a central role in the construction of new cities, transport routes and other large infrastructure projects. Although the Île-de-France region was finally created in 1976, its development has been characterised by a lack of ambition in the years since then. Since the turn of the millennium, the idea of a Grand Paris has been addressed in more detail in competitions and building programmes such as Le Grand Pari(s), the Grand Paris Express and Reinventing Paris, whereby competing urban concentration and development programmes urgently need to be coordinated.

Initial Ideas for Expanding an

Enclosed Global City

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Paris was still enclosed and separated from its suburbs by the fortifications built in 1840. The last administrative expansion took place in 1860 when Emperor Napoleon III decided to annex the suburbs within the fortifications. The first ideas for expanding the enclosed city came in the years after 1910 and were supported by the Musée social, the Association française des cités-jardins and the Société française des urbanistes. In 1911, the Seine department and the city of Paris set up an enlargement commission that published a report on the development of Paris and its suburbs. There was an initial focus on green issues. The options on the table included pocket parks, green belts and a system of parks based on the American model. An ideas competition for the regulation and expansion of Paris followed in 1919 and was modelled on the Greater Berlin Competition of 1910. The winner was Léon Jaussely, who had already won a competition for the expansion of Barcelona in 1904 and submitted a highly regarded entry to the Greater Berlin Competition together with Charles Nicod in 1909. Jaussely proposed a dual system of parks around Paris and also planned two industrial zones upstream and downstream of the Seine as well as urban expansions in the form of garden towns and suburbs. However, his proposal did not initially lead to any specific consequences.

First Ideas for Expansion Plans for

Paris in the Period to 1919

Préfecture de la Seine, Commission d’extension de Paris, Considérations techniques préliminaires (La circulation, les espaces libres), (Paris, 1913), Planche 7

The Trente Glorieuses of 1946-1975:

Big Plans, Mayor Infrastructure and Large Housing Developments

Large Housing Developments

Institut Paris Region

The institutions and economy of the Paris region underwent a catching-up process during the ‘glorious thirty’ years (Trente Glorieuses) between 1946 and 1975. The District of the Paris Region administrative structure was created in 1961 and headed

by Paul Delouvrier, a senior official appointed by President Charles de Gaulle. This was followed by the establishment of a regional planning office, the Institut d’Aménagement et d’Urbanisme (IAU), now the Institut Paris Region (IPR). A new regional development plan came into force in 1965. It broke with the radial-concentric urbanisation model and instead pushed metropolitan development along the valleys of the Seine and Marne rivers. The plan included the expansion of a regional rail system (RER) and the development of the new major Roissy Airport (also known as Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport). Five new satellite cities were to be built in order to accommodate expected population growth. This plan also paid little attention to the real Paris urban area. The construction of the Boulevard Périphérique ring road around Paris also strengthened the material border between Paris and its banlieue. However, the centre of Paris has undergone major changes with the removal of ‘unrenovated’ apartment blocks and the expansion of underground RER stations such as Les Halles and Étoile. It was possible to implement numerous inner-city urbanisme sur dalle projects in particular. This meant the complete separation of underground car traffic and above-ground pedestrian traffic, and was a particularly successful type of urbanisation in the car-oriented French city. A prominent example is the esplanade in the La Défense district, which has many of Paris’ high-rise buildings.

Greater London

Urban Development between Regulation and Deregulation

Greater London has an eventful history stretching back more than 2,000 years and currently has a population of around 8.9 million people. The port city on the River Thames has been a key centre for trade and services for centuries. It is also an important international financial centre and an outstanding centre of culture, creativity, innovation and research. The city has been growing dynamically since the 1990s, and the population is expected to increase to 10.8 million by 2041 – even if current development is marked by uncertainty due to Brexit. London’s urban development over the past 100 years reflects political trends at national and local level. Following the Second World War, the welfare state was very active and implemented social housing projects on a large scale, shaping large parts of London in terms of urban development. Unprecedented deregulation policies were pushed during Margaret Thatcher’s term as prime minister (1979 – 1990), culminating in the abolition of the Greater London Council and a planning vacuum. The Greater London Authority was established in 1998 during the Tony Blair era (1997 – 2007). It was significantly smaller and more modern. London experienced a renaissance in urban development at the turn of the millennium, and the 2012 Summer Olympics brought global attention to the regenerated east of the city. In the years since then, London has strived to transform itself into a sustainable city, promoting cycling and trying to ensure affordable rents in the housing market.

Developing Visions for the Metropolitan Area of the Future

The last century of planning history has been characterised by a desire to develop the urban region based on a major plan designed to steer through a vision that encompasses the entire metropolitan area. These plans have always addressed current social and economic developments, such as the separation of residential and industrial areas (1943 County of London Plan) or the integration of disadvantaged sections of the population (London Plan). Finally, city-wide concepts such as those for strengthening London’s high streets dealt with the planning of the outer city – where areas with a lower population density, less mixed use or long distances to access public transport require special planning ideas.

Antiqua Print Gallery / Alamy Stock Photo, ID FDNFWD

Transforming East London

5th Studio

The area of East London along the Thames River was characterised by port areas, industrial sites and working-class neighbourhoods for centuries. After the decline in these uses, transforming East London became a key urban development issue from the 1980s onwards. As with the Canary Wharf project, there were major initial setbacks due to the lack of transport links, high decontamination costs and insufficient demand. The development was given a real boost in 2005 when the city was awarded the contract to host the 2012 Summer Olympics. This decision triggered the large-scale project to build the Olympic Park in the Lower Lea Valley and paved the way for extensive projects to regenerate the surrounding neighbourhoods.