Road Transport Issues

The imperially named Kaiserplatz and Kaiserallee are now known as the far less imperial-sounding Bundesplatz and Bundesalle. The names alone speak volumes, both nationally and internationally. Main streets and their squares represent cities far beyond their centres. They give them their distinct shape. In the 1960s, transport planners transformed Kaiserplatz, then a neighbourhood square, into a traffic junction with a separating tunnel and they turned the former Kaiserallee into a motorway-like transit route. A crossing city motorway was also added to the mix. This became a model for car-oriented cities. The public realm lost its beauty and many of its functions as a result of the associated risk of accidents, noise and air pollution. The city has now been presented with a historic opportunity to regain the appeal of its main streets and squares, and locals are deeply committed to this goal.

Photo Philipp Meuser, 2020

Greater Berlin started out as a rail-oriented city, but it became more and more car-centric over time. The first car-focused plans were considered during the Greater Berlin Competition in 1910 and began taking shape during the Weimar Republic. Plans were further developed during the Nazi era and reached their peak with the planning and partial construction of the outer Berliner Ring orbital motorway. After the Second World War, the car-oriented expansion of East and West Berlin was dramatically accelerated. This resulted in the construction of a partial inner ring road in West Berlin as well as the transformation of major arterial roads. These costly urban redevelopment projects have been to the detriment of the city’s green spaces, footpaths and pedestrians as well as trams and cyclists. City streets and town squares became areas dominated by cars and traffic.

The strong development of the German automobile industry shows that we are heading towards a situation similar to that which exists in the US. Buying a car will no longer be a luxury in the future. In reality, it’s hardly a luxury today. We have to get to a situation where this is a possibility for the middle- and working-classes.

Berlin needs new ring roads in the city centre and new arterial roads out of the city. The rise in motorised traffic must be supported with dedicated motorways, as has already happened in other world cities like New York, London and Paris. Berlin needs more than just wide streets. It needs organically-designed squares that city traffic can pass through quickly, safely and conveniently.

Expanding Berlin’s transport network is absolutely necessary for economic reasons. The more transport is increased, the more business is stimulated. […] We cannot be afraid to tear down and demolish anything in our way, even if what was there was dear to us.

Gustav Böß,

mayor of Greater Berlin from 1921 to 1929

Berlin Today, Berlin 1929

Right of Way for Cars!

Berlin’s fascination with cars began very early on. Hermann Jansen was awarded first place in the Greater Berlin Competition for his entry proposing radial roads for cars so that they could ‘put the pedal to the metal’, as he put it. In 1913, preparations began for the construction of the world’s first motorway to be used exclusively by cars. Known as AVUS, the 19-kilometre, controlled-access racing circuit opened almost exactly one year after the formation of Greater Berlin. Berlin was already being planned as a car-oriented city in the later years of the Weimar Republic, but it really began to take shape during the Nazi era with the partial construction of the Berliner Ring orbital motorway. After the Second World War, both East and West Berlin opted to develop car-centric infrastructure. Initially, however, there was very little traffic in both parts of the city.

Around 1910: Cars in the Greater Berlin Competition

AM TUB, no. 20544

One of the first examples of car-oriented planning for Greater Berlin: Hermann Jansen’s winning entry to the 1910 Greater Berlin Competition envisaged five main intersection-free radial roads.

AVUS (Automobile Traffic and Training Road)

new hazardous steep curve in 1937. The new Mercedes building is visible in the background. The AVUS 100 initiative will use this photo to promote the 100th anniversary of the race track in 2021.

Photo Heinrich Hoffmann; akg / Imagno, no. 1047784

The Automobile Traffic and Training Road, better known as AVUS, was famous the world over for motor racing and speed records, but also because of the fatal accidents that happened there. It became a public access road to the Berliner Ring orbital motorway in 1940.

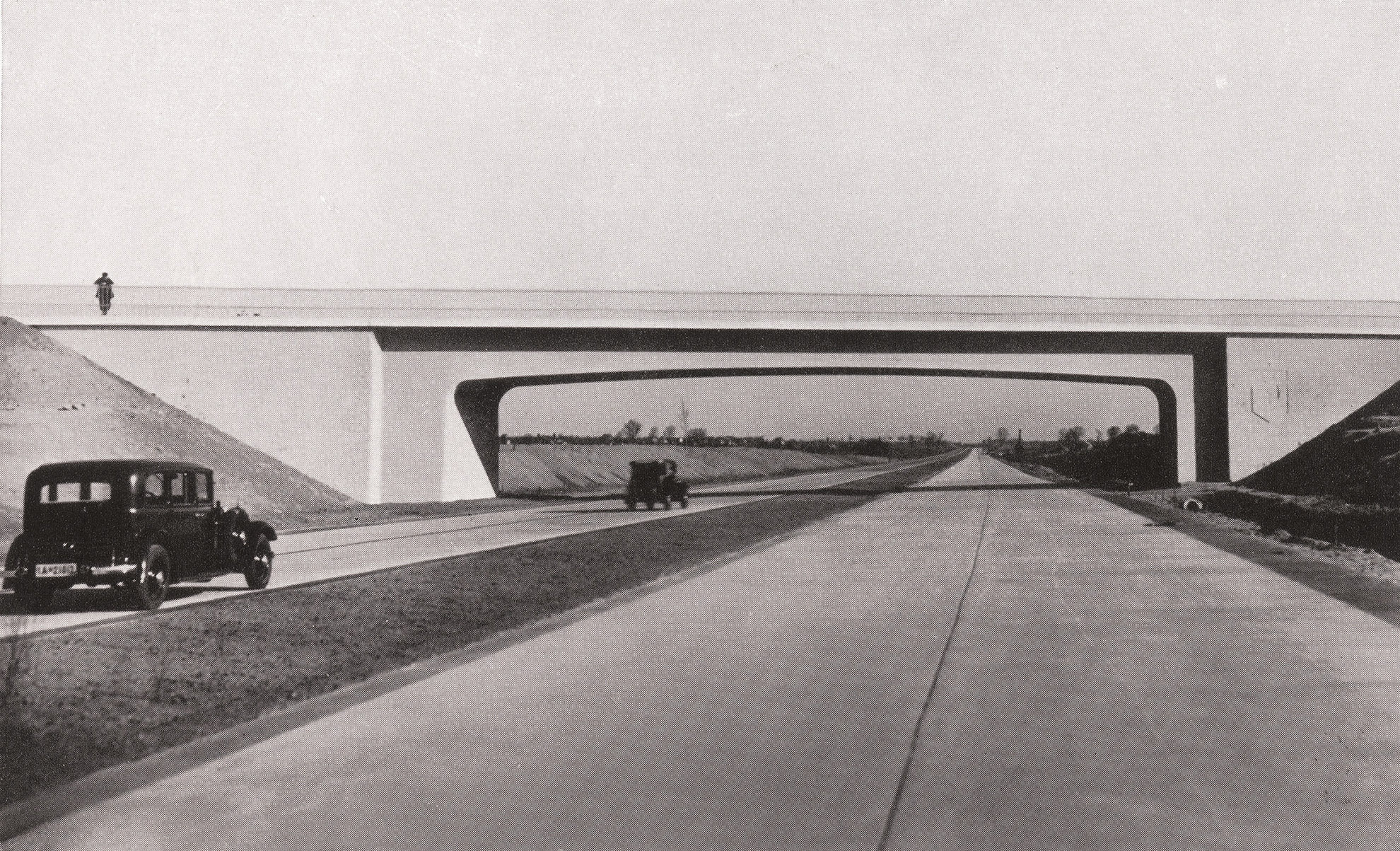

Construction of the Outer Berliner Ring

Orbital Motorway during the Nazi Era

General Inspector for the German Road Administration, Three Years of Work on Adolf Hitler’s Roads (Berlin, 1936), p. 25

The outer Berliner Ring orbital motorway is one of the most far-reaching legacies of Nazi-era urban development. Its construction marked the beginning of the era of the car-oriented city.

Construction of the Inner (Partial) Orbital Motorway

since the 1950s

Senator for Building and Housing, Planning and Constructing Transport Networks (Berlin, 1957), p. 15

In the 1950s, both East and West Berlin worked intensively on planning a motorway network for the city centre. A partial orbital motorway was built in the West Berlin section of the city.

The Loss of Town Squares along Bundesstrasse 1 Federal Highway

Bundesstrasse 1 federal highway, formerly Reichsstrasse 1, is one of Germany’s most important national roads, previously linking Königsberg with Aachen. It became the city’s most important road after the formation of Greater Berlin: It connected the two former residences of the Hohenzollern royal family in Berlin Mitte and Potsdam, ran into the city centre along the main shopping streets and crossed an extensive residential area in the southwest of the city. The car-oriented expansion of the city has largely preserved this famous road as a radial urban street, but there has been considerable damage caused in some places, including the empty expanse at Molkenmarkt, the no less daunting expanse at Innsbrucker Platz and the nameless space in front of the car park at the Steglitzer Kreisel building.

Molkenmarkt

Photo Philipp Meuser; BMA, Meuser 2013, no. 52

How many Berliners know that Molkenmarkt is the centre of the oldest part of the city? Today it is an empty expanse solely dedicated to the car, home only to multi-lane streets and parking spaces. This is one of the negative sides of Greater Berlin.

Innsbrucker Platz

akg / euroluftbild.de, no. 5236335

Innsbrucker Platz, which was originally a town square, has been a sprawling, car-dominated intersection since the 1970s. The city’s Ringbahn circular line, U-Bahn and motorway all intersect here. There are also some roads, including Bundesstrasse 1 federal highway, that lose ground here.

A Nameless Area to the South of the Steglitzer Kreisel Building

Photo Thomas Spier, apollovision

It’s a little-known fact that the Steglitzer Kreisel building was built on what was until the 1960s the village of Steglitz. Since then, the area south of the building in front of the multi-storey car park has become a vast, nameless space that serves only traffic, most of which comes from the Western Tangent motorway.

The Tedious Search for the Streets and Squares of the Future

Dismantling car-oriented city structures is an inevitable step in the process of developing a sustainable city. It is widely agreed that it is necessary to further expand Berlin’s public transport network. It is also undoubtedly the case that measures must be taken to restrict the number of private cars on the city’s streets. The new Berlin Mobility Act enhances the status of bicycle and pedestrian traffic, at least in principle. However, the scope of Berlin politics is limited and Brandenburg must always be taken into account. The question is, what should the streets and squares of the future look like? And how can we balance the needs of all road users? The shift to more sustainable modes of transport requires a lot of new ideas, a great deal of persuasion and a driving force behind the implementation – we must go beyond laws and proclamations. The crowning achievement of these efforts will be new, sustainable main streets that we cannot yet imagine.

Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection / eveimages