The Creation of Greater Berlin

The Greater Berlin Act was passed by the Prussian Parliament on 27 April 1920 and came into effect on 1 October 1920. The passing of the act came just a month after the Kapp Putsch at a time when both Berlin’s and Germany’s future was uncertain. It coincided with the severe crisis that followed the First World War and the end of the Spanish Flu pandemic. It was one of the most important events in Berlin’s 800-plus years of history and came as a result of decades of disputes between the individual municipalities in the greater Berlin area as well as between Berlin and Prussia.

Although Greater Berlin wasn’t created until 1920, it already existed socially, economically and structurally for some time before then. Industry, the military and the neighbourhoods favoured by the wealthy had all increasingly been moving to the edges of the old city of Berlin since the 1880s. Siemens set up a base in Spandau, Borsig set up in Tegel, while AEG moved to Hennigsdorf and Oberschöneweide.

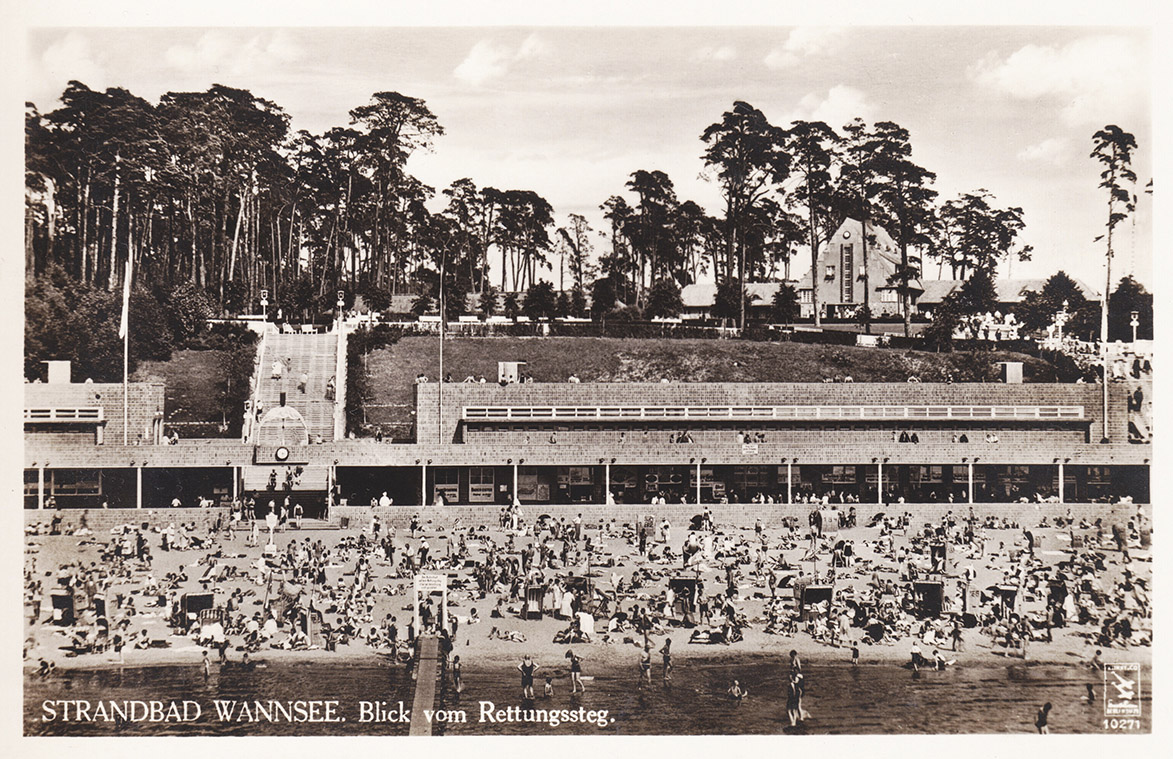

The military also began to occupy more of the city’s surrounding areas, including Döberitz, Jüterbog, Kummersdorf and Wünsdorf. New, grand residential areas emerged in the west (Westend), north (Frohnau), east (Karlshorst) and particularly in the southwest (from Grunewald to Wannsee). Large numbers of unskilled workers remained in the city centre, especially in Moabit, Wedding, Friedrichshain, Kreuzberg and Neukölln. The old town became the city centre. Commuter railway lines, natural and artificial waterways and large arterial roads held the new city together.

The most important event in Berlin’s history is the city’s incorporation in 1920.

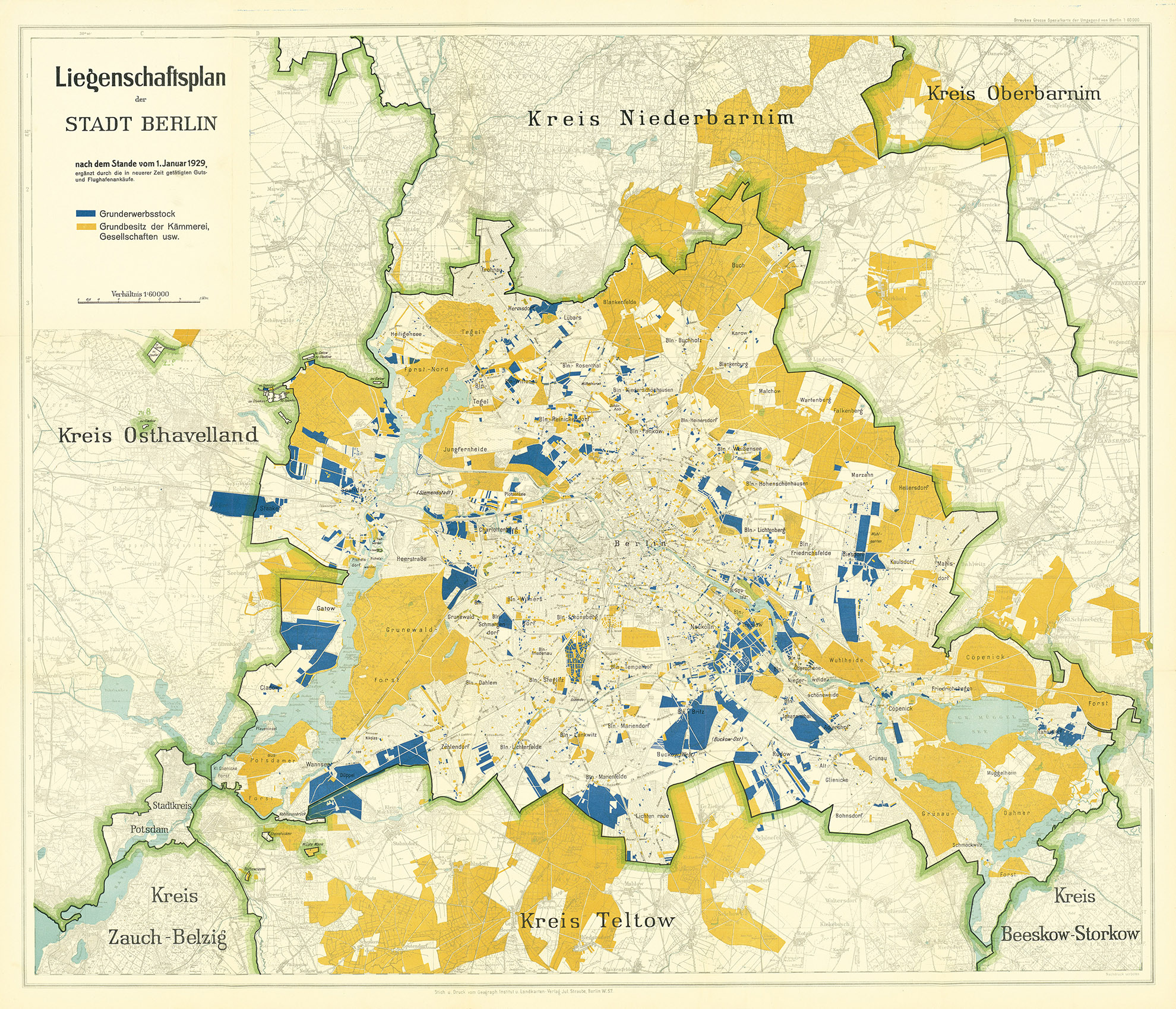

The new Berlin was formed in 1920 by consolidating 8 cities, 59 rural communities and 27 agricultural estates – a total of 94 municipalities. It became a single municipality. […] Greater Berlin is subdivided into 20 administrative districts.

There was constant friction between the former individual municipalities of Greater Berlin […]. The municipalities tried to steal efficient taxpayers from one another […]. The act passed on 27 April 1920 put an end to the conditions that allowed this to happen.

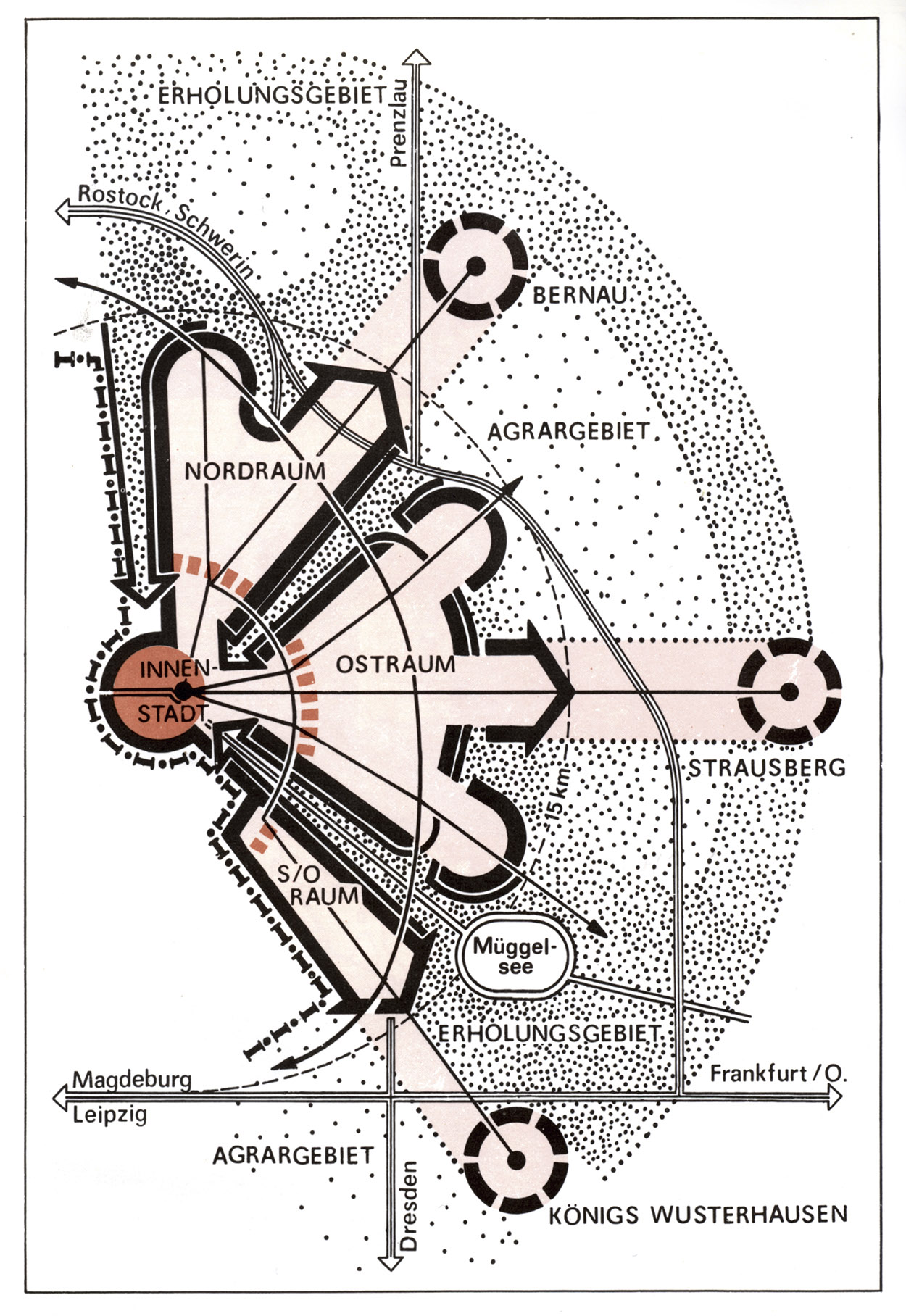

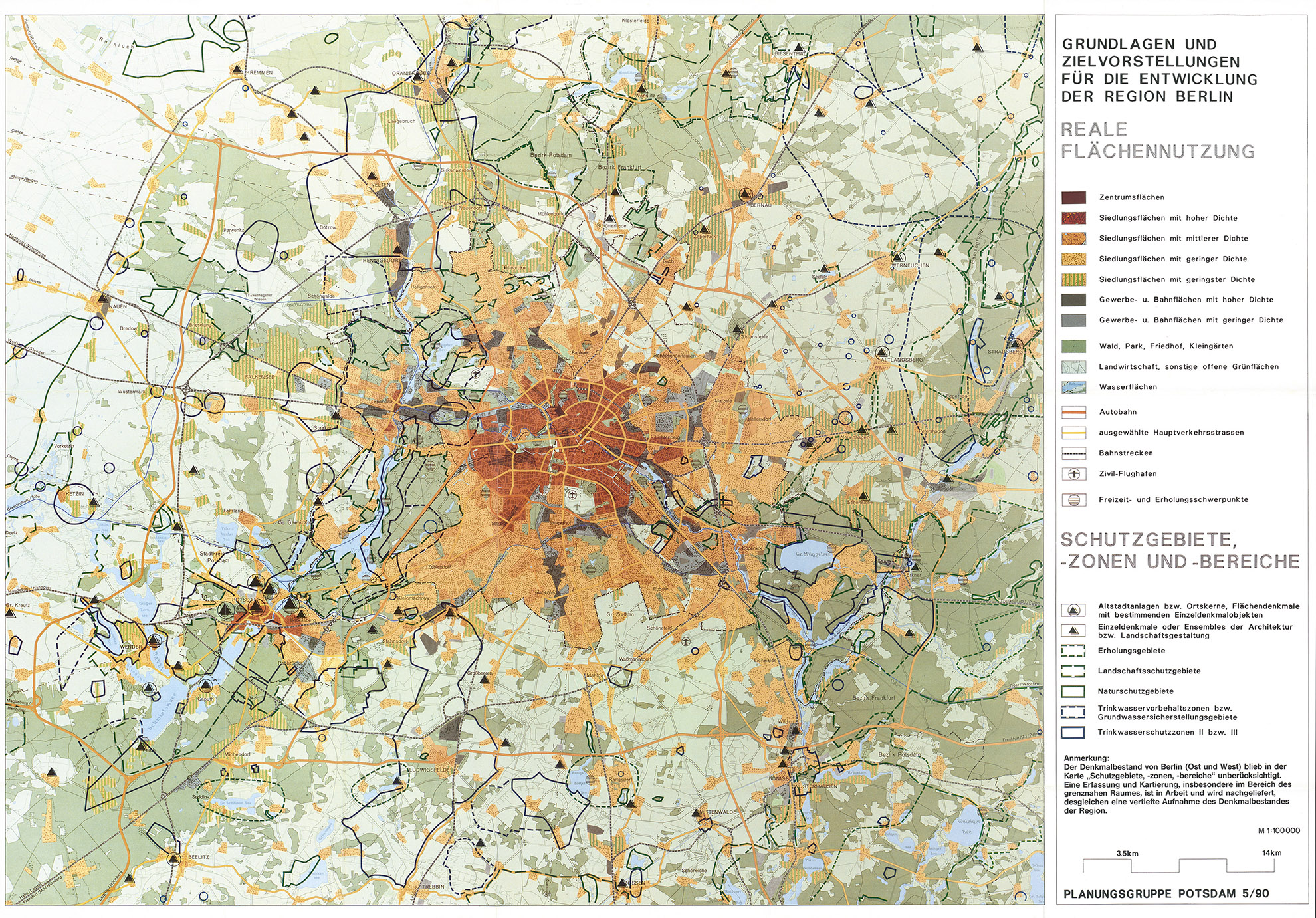

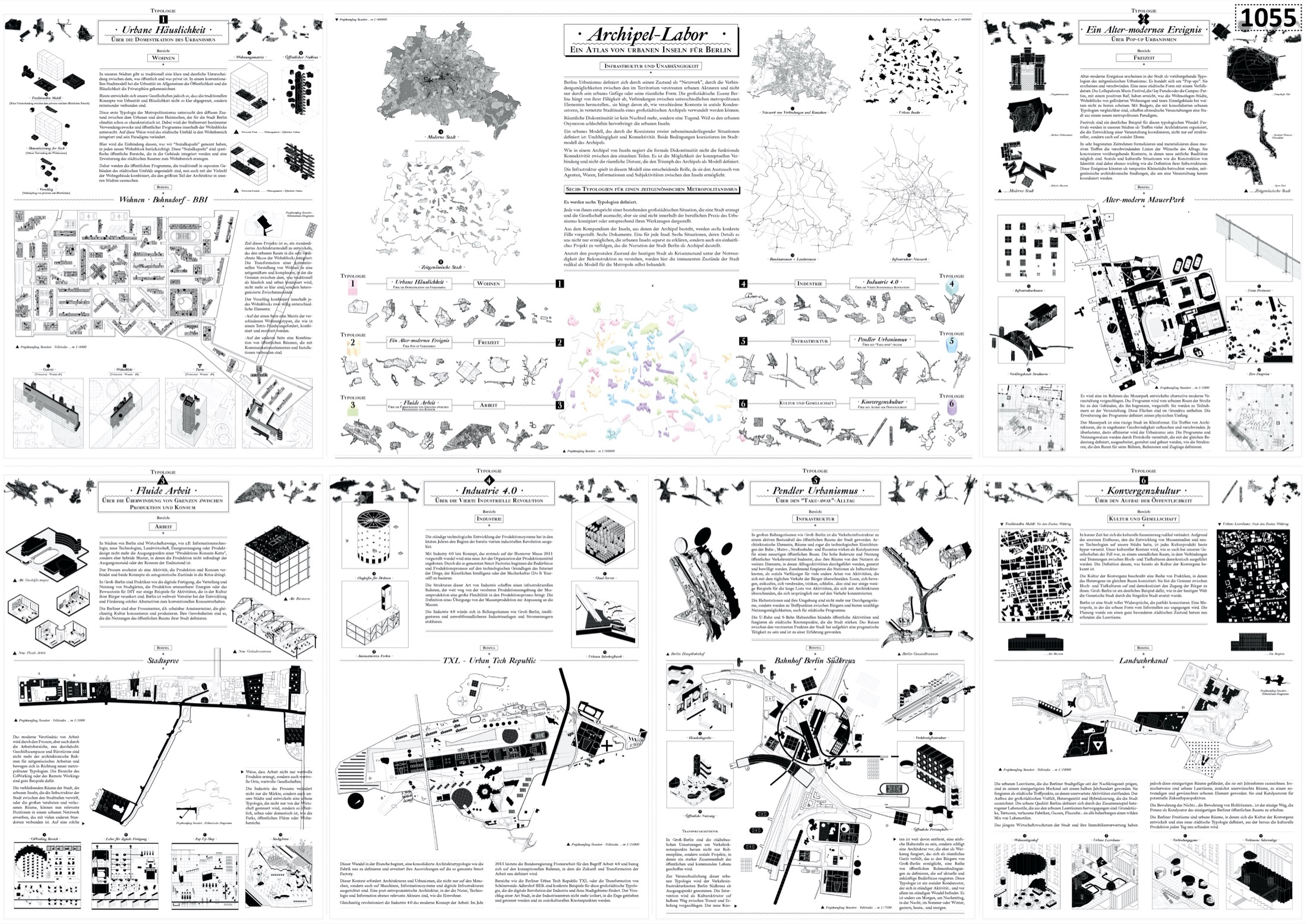

It is debatable whether the current city boundary of Berlin will be sufficient for the future.

Gustav Böß,

mayor of Greater Berlin from 1921 to 1929

Berlin Today, Berlin 1929

On the Eve of the Creation of Greater Berlin:

The Spanish Flu Pandemic of

1918 – 1920

A chart showing mortality rates related to Spanish Flu in New York, London, Paris and Berlin between June 1918 and March 1919. The Spanish Flu killed more people worldwide than the First World War, but had been largely forgotten until the coronavirus pandemic restored it to public attention. Somewhere between 27 and 50 million people lost their lives over three waves of infections between spring 1918 and 1920. More than 40,000 people in the Greater Berlin area died from the disease. At that time, municipalities like the Prussian state were unable to implement measures to contain the pandemic. The chart shows the peak of the pandemic in the autumn of 1918. Note that it is missing continuous data from Berlin.

The Kapp Putsch in March 1920

The Kapp Putsch by Else Hertzer. Germany’s young democracy appeared to be faltering in mid-March 1920, just over a month before the passing of the Greater Berlin Act. The Ehrhardt Brigade marched from Döberitz to Berlin via the Heerstrasse (now Bundesstrasse 5 federal highway). The soldiers wore a white swastika emblem on their helmets. The imperial government managed to flee to Dresden and later moved on to Stuttgart. Wolfgang Kapp, an East Prussian civil servant, declared himself the new Chancellor. The subsequent general strike was the largest in German history and ultimately forced the putschists to surrender. Hertzer’s painting shows soldiers on a Berlin street at night. The diffuse light shining aggressively from the vehicle headlights spreads fear.

Greater-Berlin

Hardly worth reporting

The birth of Greater Berlin was not a brilliant event that dominated the front pages of the newspapers. Neither on April 27, when the Prussian State Assembly approved the merger by a wafer-thin majority, nor on October 1, when Greater Berlin became a reality. On the contrary: the decision in favor of Greater Berlin was worth only a scrawny piece of news, which hardly differed from newspaper to newspaper. The headlines were delivered by other events, such as the consequences of the Kapp Putsch and the international situation.

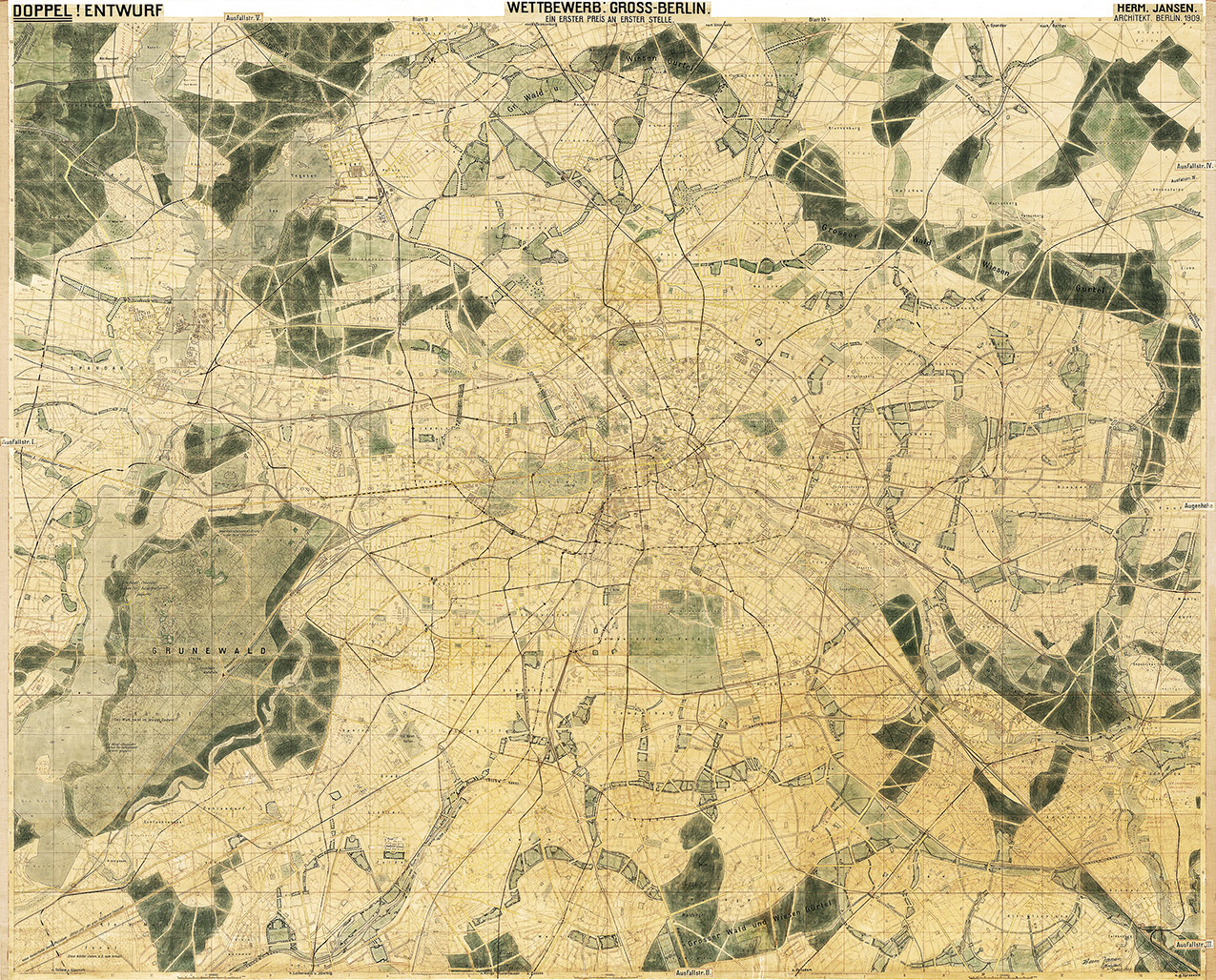

Champions for Greater Berlin

The creation of Greater Berlin did not come out of nowhere. Great efforts – and great personalities – were needed in order to overcome tough resistance. It is astonishing that some of the key figures have been forgotten. Mayor Martin Kirschner was a huge proponent of Greater Berlin and served as chairman of the jury for the Greater Berlin Urban Planning Competition of 1910, and Greater Berlin would not exist with the strategic skills of Mayor Adolf Wermuth. Finally, it was Mayor Gustav Böß who determined the fate of the city during the turbulent 1920s.

Largely Forgotten:

Mayor Martin Kirschner

bpk, no. 30034621

Martin Kirschner served as mayor of Berlin between 1899 and 1912 during a period of turbulent growth and campaigned for the creation of Greater Berlin. He influenced the results of the Greater Berlin Competition (1908–1910) through his role as chairman of the jury. During Kirschner’s time in office, the idea of Greater Berlin as a single municipality did not catch on and it was only possible to set up a Joint Authority in 1912.

Largely Forgotten:

Mayor Adolf Wermuth

Photo Willi Römer; bpk, no. 700141738

As mayor of Berlin from 1912 to 1920, Adolf Wermuth fought vehemently for the creation of Greater Berlin as a single municipality. It is thanks to Wermuth’s strategic skills that Berlin has the scope and the two-tier administrative organisation that we still know today.

Largely Forgotten:

Mayor Gustav Böß

Photo Georg Pahl; German Federal Archives, no. 102-07938

Gustav Böß, a local politician with the German Democratic Party (DDP) and city treasurer, was elected mayor in 1921, just one year after Greater Berlin was created. He was the key decision maker in the municipal urban development process for the single municipality during the Weimar Republic until the end of his term in 1929.

Renée Sintenis:

A Little Bear for Greater Berlin

The new, bigger Berlin needed a new heraldic animal that would differ from the bears of the old Berlin. It needed an animal of the Weimar Republic to distance it from the empire. Renée Sintenis created Berlin’s most famous bear in 1932. Her bear is a clumsy, dishevelled little creature, hardly awe-inspiring, but lovable nonetheless. A slightly modified 1956 version of the bear standing on its hind legs with its front paws raised has served as the Golden Bear award at the Berlinale film festival since 1960.

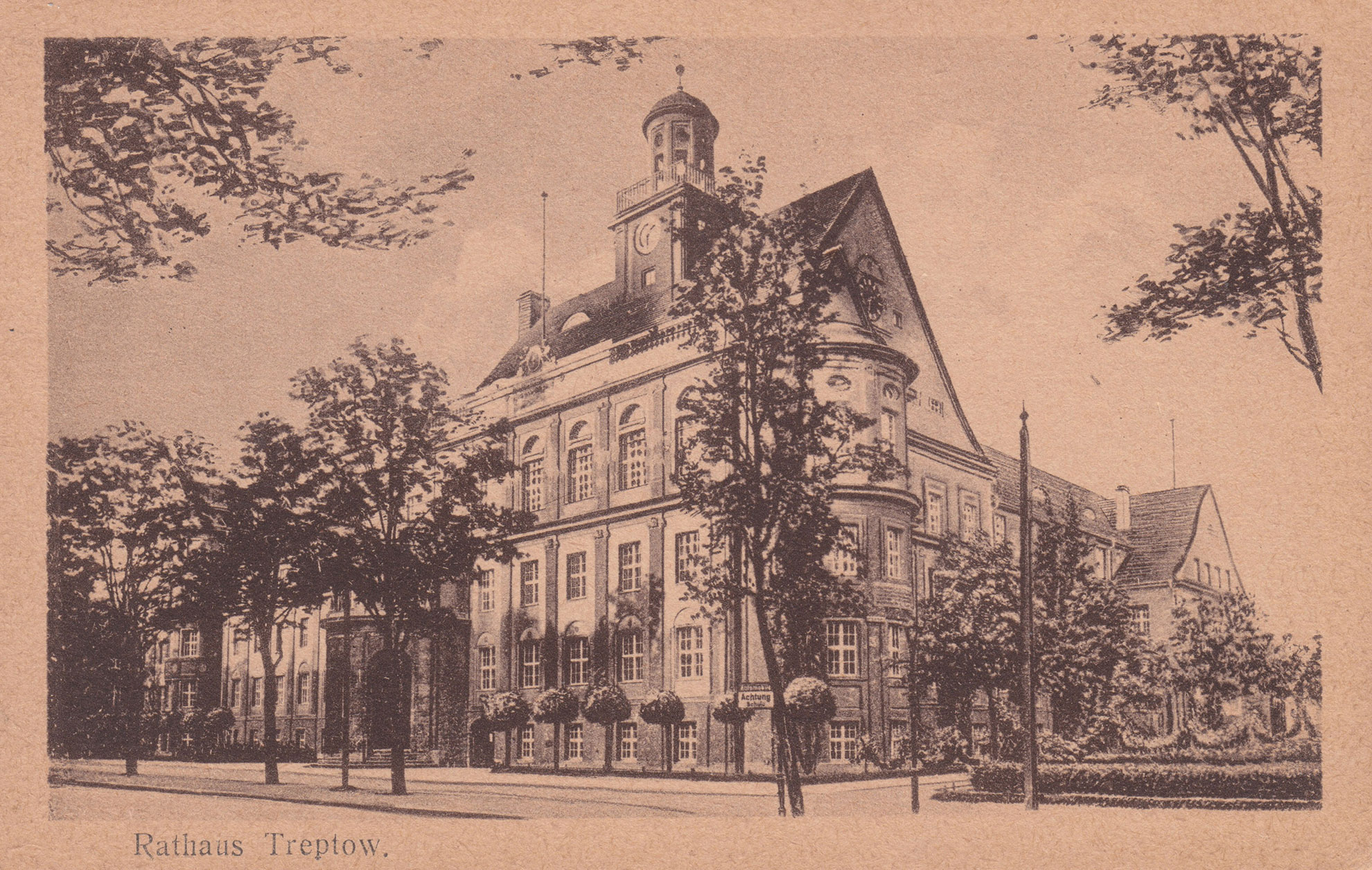

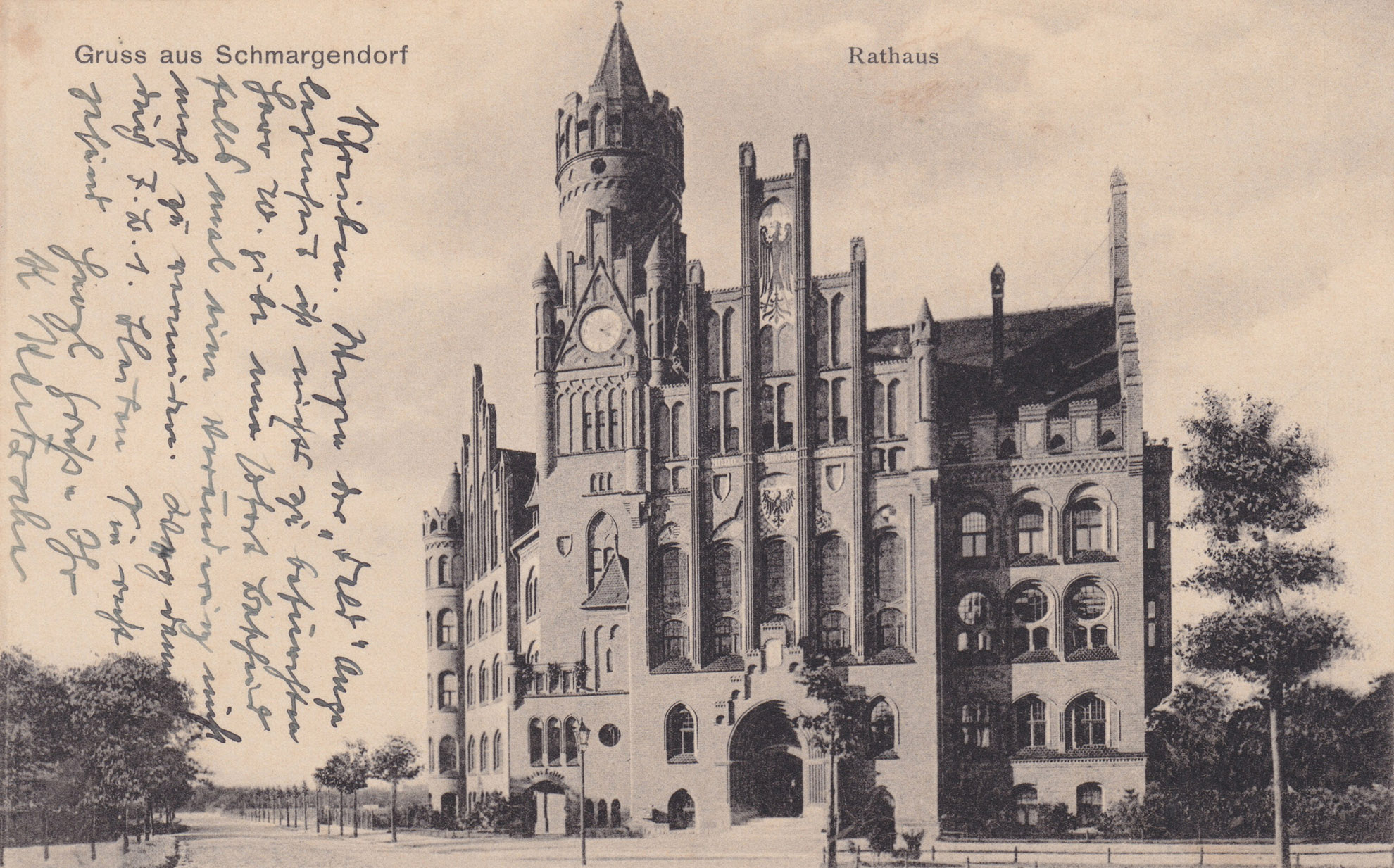

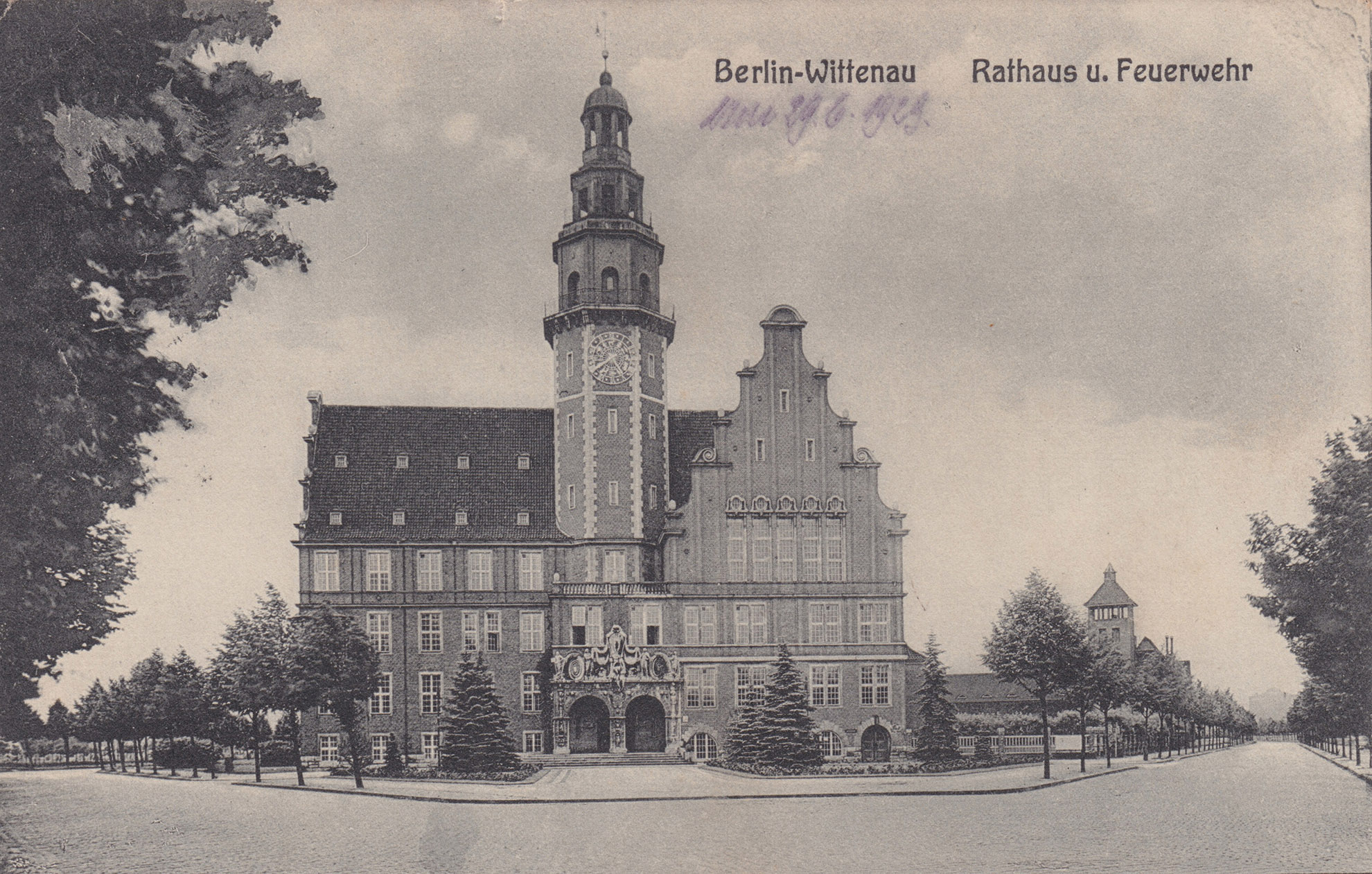

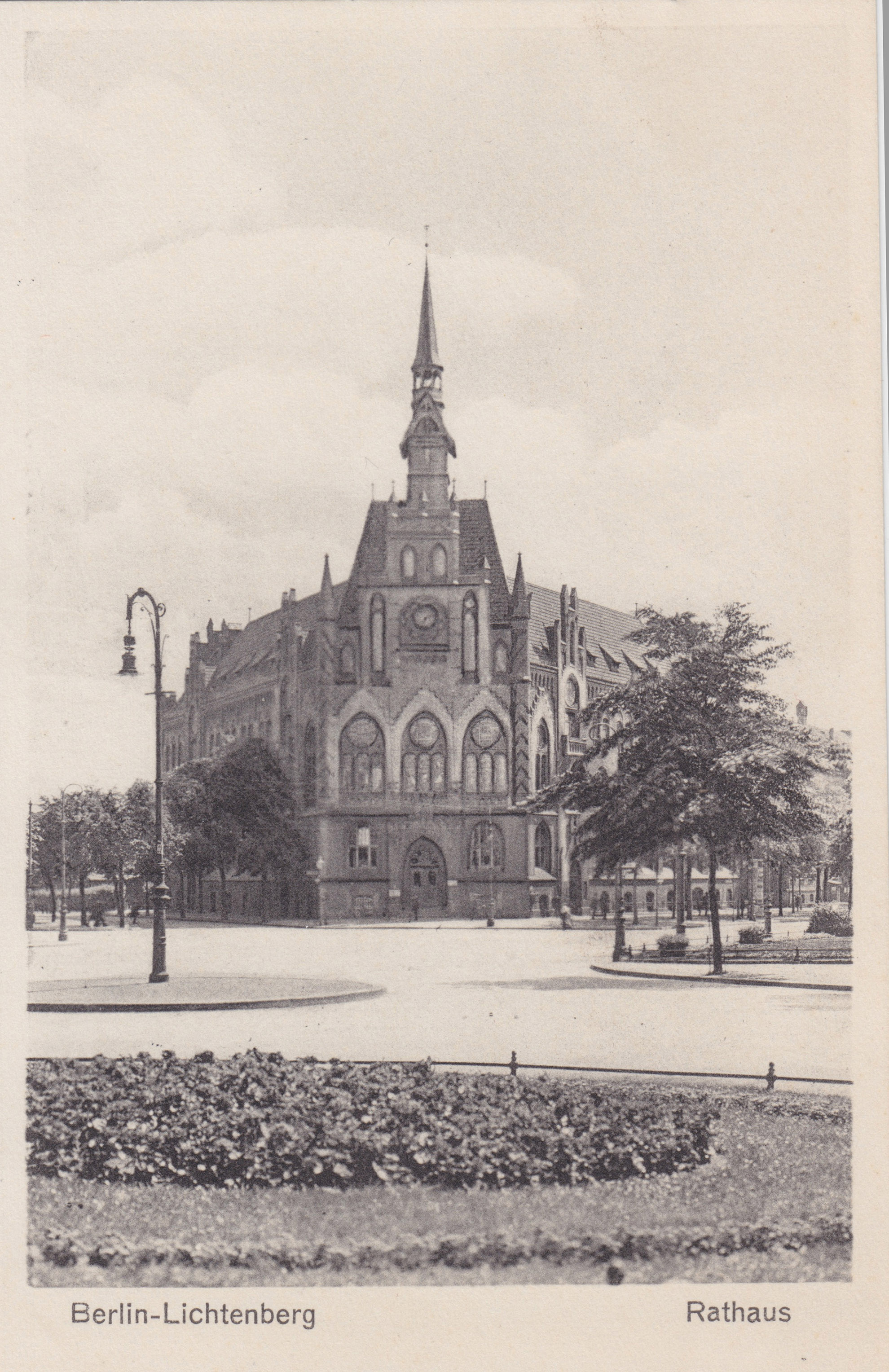

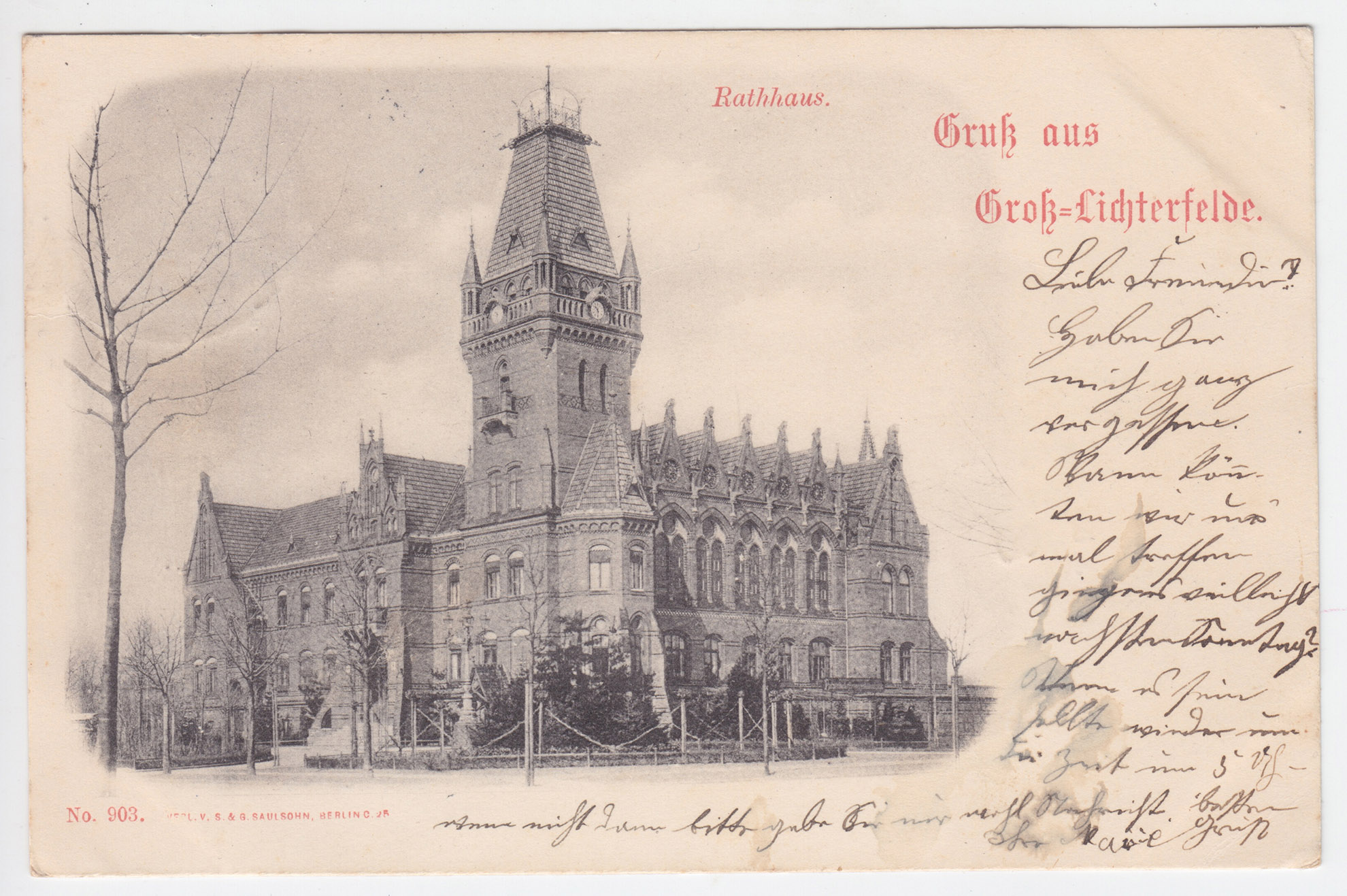

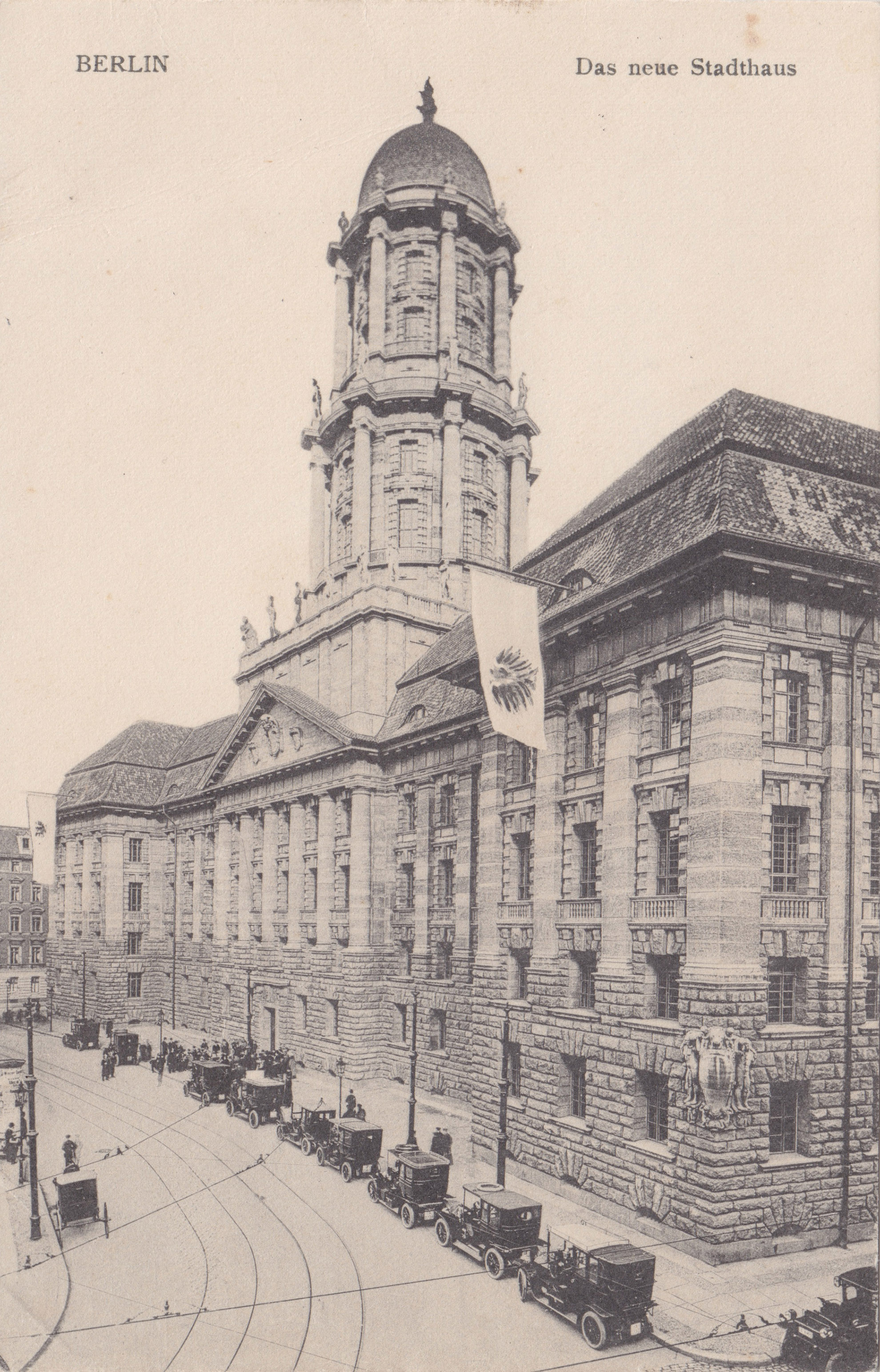

Town halls aplenty

The countless more or less grand town halls dotted throughout the city and its metropolitan area show that Greater Berlin came as a result of consolidating many towns and municipalities. Back in 1920, most of the town halls were still relatively young, dating from the imperial era. No other major European city has as many town halls as Berlin. They are evidence of the fact that the city has overcome municipal fragmentation, but also that the municipalities have lost their independence.

Wilmersdorf Town Hall (1894), Postcard

Wannsee Town Hall (1901), SSB, no. 2014-2026, 94-1

Treptow Town Hall (1910), Postcard

Steglitz Town Hall (1897), Postcard

Spandau Town Hall (1913), Postcard

Schöneberg Town Hall (1914), Postcard

Schmargendorf Town Hall (1902), Postcard

Reinickendorf Town Hall (1911), Postcard

Pankow Town Hall (1903), Postcard

Nikolassee Town Hall (1913), Postcard

Neukölln Town Hall (1914), Postcard

Lichtenberg Town Hall (1898), Postcard

Köpenick Town Hall (1905), Postcard

Lichterfelde Town Hall (1894), Postcard

Friedenau Town Hall (1916), Postcard

Charlottenburg Town Hall (1905), LDA, no. 1158-1959

Berlin Town Hall (1871), Postcard

Old City Hall (1911), Postcard