Planning Culture

Urban development in Berlin has always been the subject of intense debate. Participants have included not just planning professionals, politicians and the administration, but also representatives of civil society and commerce. The debates have been about targets, instruments, institutions and funding. And so also about parties with and without influence. Even Greater Berlin itself was divisive. After 1920 new battlefronts emerged: districts versus municipal authorities (Senate) and Greater Berlin versus Brandenburg. In the 1970s and 1980s the urban conflict reached its climax. The fall of the Wall was an occasion for ferment: Berlin equals protest! Today the organisation of the relationships between the districts and the senate, between Berlin and Brandenburg, and sometimes even between Berlin and the federal government, remains on the agenda. So too is the creation of bodies, plans, and platforms to regulate growth – always in dialogue with representatives from civil society and the economy. The capacity for action that gradually brings about stability must be developed.

The administrative organisation of the new Berlin has two special features: first of all, in terms of budget and administrative policies, the districts are to a great extent autonomous, and, second, there is now a quick and easy working connection between the municipal authorities and the district administrations […].

[…] It can’t be denied that the administrative organisation is in no way ideal. It can and must be substantially simplified and improved.

In the democratic country of today the citizen is the helmsman and the officials are the oarsmen of the ship of state.

The personal responsibility and initiative of the citizenry is by no means suspended by the central administrative organisation.

Berlin’s administration problem has only been partially solved. […] It is generally acknowledged that a simplification of Berlin’s city constitution and administration is overdue and very much in the interest of the population.

The economy and the municipal administration have to work together, rather than against each other.

Gustav Böß,

mayor of Greater Berlin from 1921 to 1929

Berlin Today, Berlin 1929

Urban development and power

In terms of its urban development, Greater Berlin has travelled a bumpy road. The creation of the metropolis during the imperial era was predominantly driven by commercial interests – large land companies, private transport firms – with the financial backing provided by the major banks. The public authority only set the ground rules, through the Hobrecht Plan in 1862, the Prussian Vanishing Line Law in 1875, and the building regulations, which were corrected again and again for Berlin and the environs. In the Greater Berlin of the Weimar Republic everything altered: the local authority now took the lead in urban development, for both housing construction and infrastructure (transport, energy provision and parks). For this, they relied on their own firms or ones they controlled. During the National Socialist period this stopped, and the central government took up the baton. After the Second World War, state-directed urban development continued in principle, albeit in a complicated form: Although the influence of the Allies, the central government, and the municipality varied over the decades of Germany’s division, each side was dependent on the support of their respective state. It was only after the Reunification that private-sector urban development regained ground.

Private-sector Urban Development

Georg Haberland, on his seventieth birthday on 14 August 1931. As director of one of the most influential land companies in Berlin, the Berlinische Boden-Gesellschaft (BBG), Haberland developed entire districts, such as the Bayerische and the Rheinische Quarters. As an entrepreneur, politician, and author he was without doubt the most important representative of private-sector urban development in Berlin. A lesser-known fact is that, after the First World War, he was also active on a large scale during the period of local economic development, but only on behalf of others. The projects included the Neu-Tempelhof housing development, a big residential quarter south of the Südwestkorso, the Karstadt Building on Hermannplatz, and Saint Joseph’s Hospital in Tempelhof, and the BVG tram stations. Following his death in 1933, Haberland’s firm was ‘Aryanised’ step by step, and his son Kurt was ousted from the board of directors, imprisoned in 1941, and murdered in the Mauthausen Concentration Camp in 1942.

Local Economic Urban Development

Martin Wagner, around 1930. Wagner was a passionate advocate of municipally managed urban development even before he became head of Berlin’s planning and building control office in 1926. Once in post, he sought the participation of private investors. However, his commitment to building new housing, a car-oriented city, the expansion of the Wannsee Lido, and a radical conversion of Berlin’s old town were only partly crowned with success. He witnessed the failure of his work, in particular in the years towards the end of the Weimar Republic, and not only because of the economic crisis. After 1933 he tried to adapt to the new rules of urban development being introduced by the National Socialists. For example, in 1934, writing under a pseudonym in the Deutsche Bauzeitung, he called for the appointment of a State Commissioner for the Renovation of the City of Berlin and a Führer of the City of Berlin. Martin Wagner left Germany in 1935.

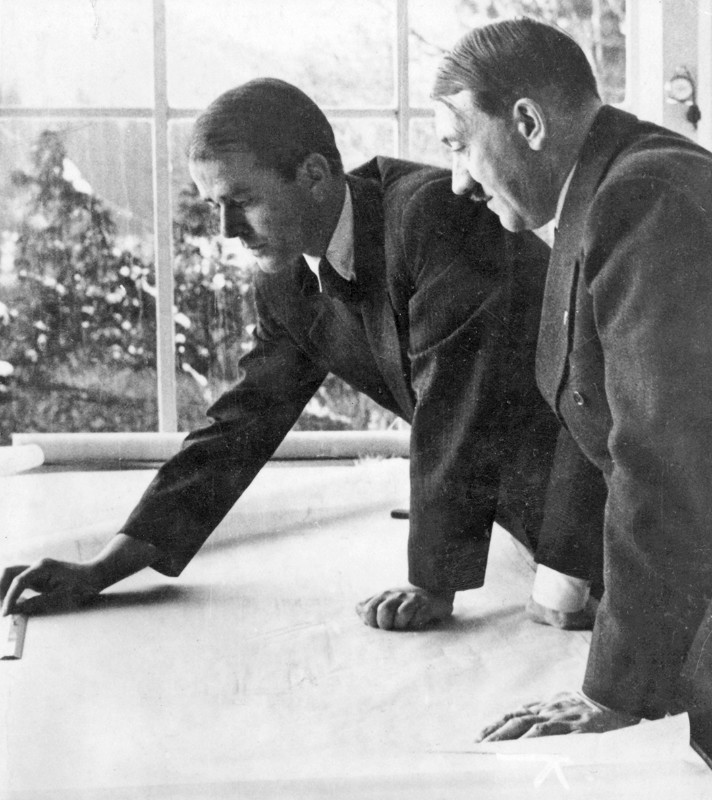

Public-sector Urban Development

Albert Speer, around 1938. As General Building Inspector for the Capital of the Reich, Speer was responsible for the planning of Greater Berlin from 1937 to 1945. He had special powers, such as access to financing, and could ignore the wishes of local authorities or even the Reich capital itself. The boundaries of Greater Berlin were irrelevant for him. His plans extended to the outer reaches of the orbital motorway. The general building inspector’s plans for the new centre of Berlin were notorious. The largest project on the outskirts, the so-called Südstadt running along the southern axis, is less well known. Out of all the leading figures during the Nazi dictatorship, he most embodied a public-sector urban development that was premised on blocking municipal autonomy and the unflinching expropriation of private property. His plans rendered him jointly responsible for the crimes committed under National Socialist rule.

The Contradictions of Greater Berlin

It was obvious from the beginning: the Greater Berlin Act of 1920 did not adequately regulate the relationship between the municipal administration and the districts, in particular the ties between Greater Berlin and the province of Brandenburg. These design flaws were inherited by the subsequent polities and administration and still exist today. They are especially disruptive for managing a growing metropolis. The proposals put forth by the Commission for the Improvement of Overall Urban Management – a body of experts that presented its final report in summer 2018 – must be brought to the fore and augmented by political reforms. The proposal for a regional council, put forward by the Future Berlin Foundation (Stiftung Zukunft Berlin) also warrants attention. Unless Greater Berlin’s design flaws are overcome, any good urban-development strategy applied in the metropolis will grind to a halt through institutional gridlock.

Districts versus Municipal Administration/Senate

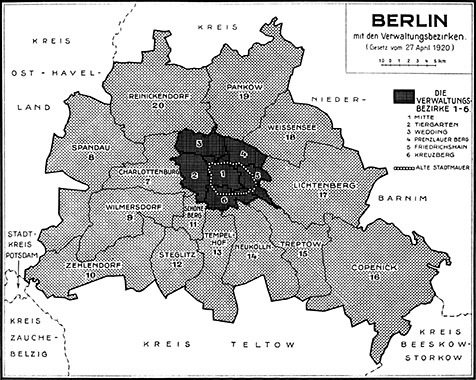

A map of Greater Berlin published in 1931. From the outset, the gigantic city was divided. Its 20 districts reflected the political and spatial developments before 1920. Among them were the six inner districts of the old town, the internal boundaries of which were neatly drawn. However, during the final negotiations, the division of responsibility between the municipal administration and the districts was left unclarified, so as to guarantee a majority in the Prussian State Assembly. This lack of precision remains a problem today.

The Great Battle for Urban Development

From its inception, Greater Berlin was a capital of protests, a centre of the socio-political battle for the right urban development. Many of these struggles have been forgotten today. One example is the great controversy around the development of the western side of Tempelhofer Feld in 1910. The issue was, as ever, affordable housing – an issue that extended far beyond the years of the Weimar Republic. The battles for the city reached a climax in the 1970s and 1980s. The wholesale redevelopment in the East and West was moving up the agenda, and the number of cars on the roads was becoming a problem. After the Reunification, the quarrels continued with referendums, such as those that contributed to deciding the fate of the Mediaspree project and the development of Tempelhofer Feld. Social controversy is necessary; it is good for the metropolis – but only when it constructively seeks to find the best way towards a sustainable future.

Down with High-density Development in Tempelhofer Feld!

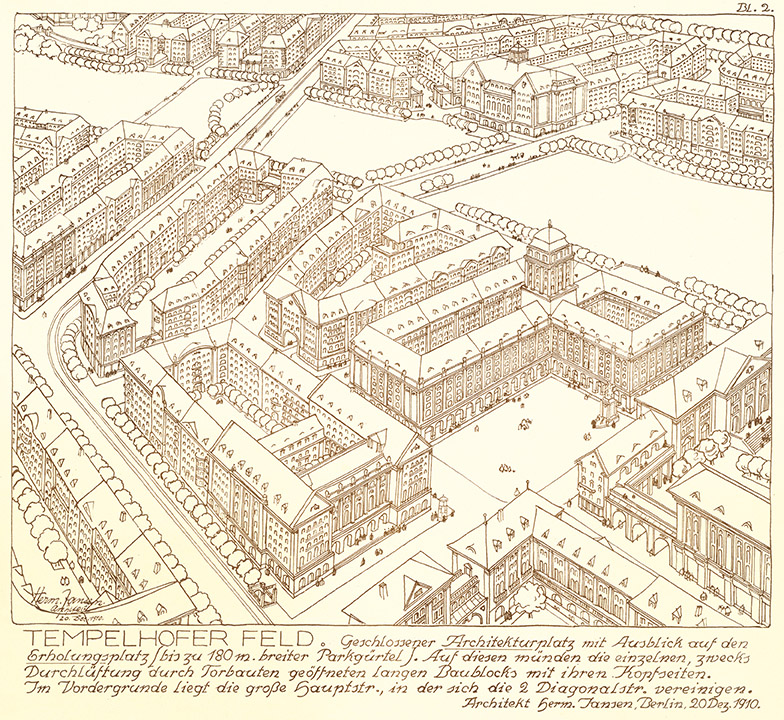

Hermann Jansen’s plan for Tempelhofer Feld, entry to the Greater Berlin Competition 1908–1910. Behind this evocative plan a fierce quarrel raged; the issue at the time was the development of the western side of Tempelhofer Feld. The parties involved were the Military Treasury – the owner of the parade ground – the City of Berlin, the Municipality of Tempelhof, the District of Teltow, the Province of Brandenburg, and some large banks and land companies. The subject of the dispute was not just the question of who would gain the upper hand, but also what level of density the new development should have. The project therefore formed part of the arguments over the direction of Greater Berlin’s urban planning. The Military Treasury prevailed, implementing a high-density built area, which contributed to a high sale price in 1910. But its victory was pyrrhic: after the First World War, a suburban development policy was adopted.

For Greater Berlin!

Poster with a drawing by Käthe Kollwitz, 1912. The idea of Greater Berlin was the subject of a bitter disagreement long before the First World War. One of the parties involved was the Propaganda Committee for Greater Berlin. Their poster, seen here, announced an assembly to raise objections to the drastic housing shortage in Berlin. The police commissioner had the poster banned because of its accusatory motif.

Down with Rent Increases!

Rent strike in Köpenicker Strasse, 23 September 1932. The tenants protested under the motto ‘First food, then rent’. They hung banners featuring the hammer and sickle, as well as the swastika, from rear-courtyard windows. At the end of 1932 the whole of Kösliner Strasse, the reddest street in Wedding, the reddest district, was on strike. The less-than-successful rent strike towards the end of the Weimar Republic was the biggest protest of its kind in the history of Berlin.

Down with Wholesale Urban Renewal!

West Berlin

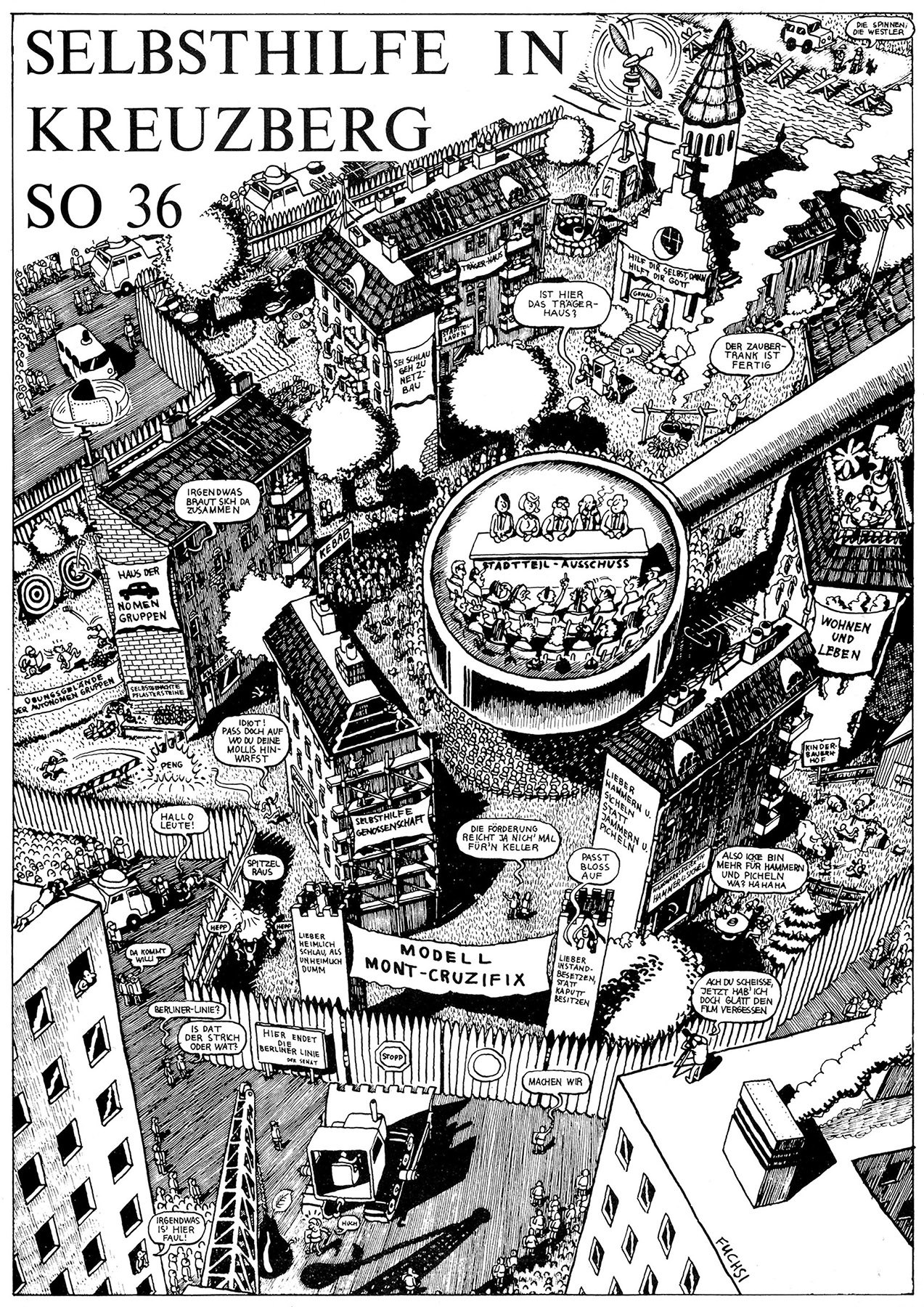

Poster: ‘Self-help in Kreuzberg SO 36’. In addition to posing a threat to the old building stock in Wedding and other districts of West Berlin, the wholesale urban renewal of the 1970s and 1980s represented a challenge to the lifestyles of the residents. As more and more streets were demolished, an unprecedented protest welled up, supported by a broad alliance of those directly affected, political initiatives, and intellectuals. At the same time, many initiatives such as self-help projects were established and filled the endangered buildings with new life.

Down with Wholesale Urban Renewal!

East Berlin and Potsdam

Poster for the exhibition ‘Find the Best for the City’, 1989. In East Berlin and other cities of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) – like Potsdam – protest against the decay and demolition of pre-Second World War buildings increased in the 1980s. It reached its peak in 1989 and was a major factor in the collapse of the GDR. Held in summer 1989, the ‘Find the Best for the City’ exhibition criticised the deterioration and threats to knock down of the second baroque city expansion. It was shown again in 2019 at the Potsdam Museum. This exhibition, three decades later, did not receive the attention it deserved in Berlin.

Down with the Car-oriented City!

Western Tangent Citizens’ Initiative

Demonstration of the Citizens’ Traffic Policy Committee (known as the Western Tangent Citizens’ Initiative since 1974) in West Berlin on Kurfürstendamm, July 1972. This protest was the first large-scale demonstration opposing the destruction of the city in the framework of the planning for a car-oriented Berlin. The focus was the fight against more city motorways, with the Western Tangent on the front line.

Sink the Mediaspree!

‘Three Cheers for the Investors’ campaign, July 2008. The protests in Berlin continued after the Reunification. They were increasingly organised in opposition to rent increases, as well as a more automobile-friendly city. A highly professional protest which influenced later social confrontations concerned one of the most influential development regions in the new Berlin in the 1990s: the eastern Spreeraum, the region around the River Spree. The Sink the Mediaspree (Mediaspree versenken) group took a stand against various private investors for developing the river banks. But in spite of a successful local referendum in 2008, their demands were only partially implemented.

For the People:

100% Tempelhofer Feld!

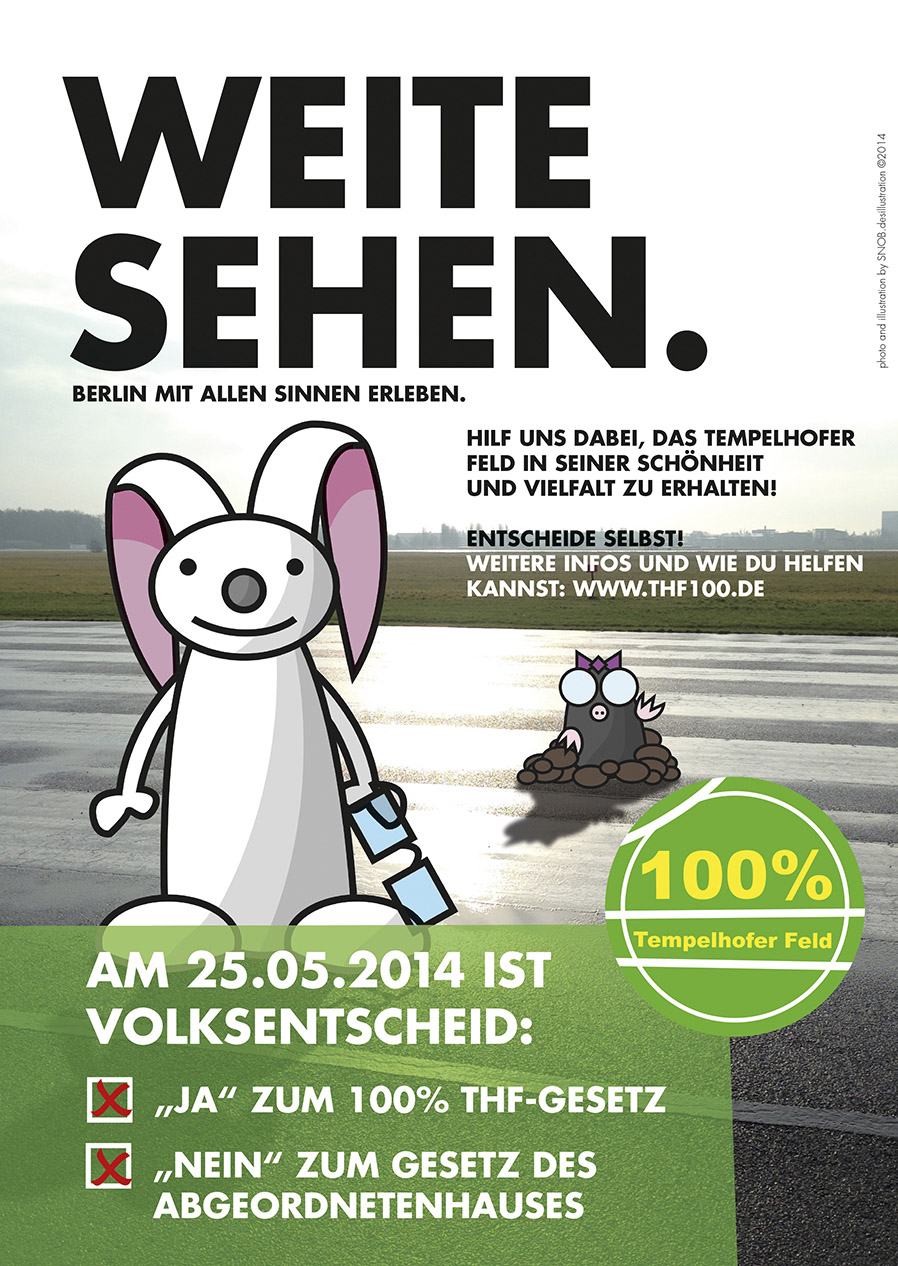

Poster by the citizens’ initiative 100% Tempelhofer Feld, 2014. When Tempelhof Airport was shut down in 2008, the Senate had no convincing ideas for further development of the area. After violent confrontations about a partial development on the edge of Tempelhofer Feld, a citizens’ initiative was founded in 2012. The group, with partners in both politics and wider society, successfully organised a popular referendum. This resulted in an astonishingly clear mandate for an ‘inner-city open landscape’.

For Better Streets and Squares!

Advertising for a party on Bundesplatz, the centrepiece of Bundesallee, from October 2015. The celebration was initiated by the Initiative Bundesplatz and supported by the Council for European Urbanism Deutschland. Bundesallee is not just any street and Bundesplatz is not just any square. In addition to their distinctive names, they comprise one of the most striking urban-developmental features in Berlin’s layout. These two locations – along with the city motorway – are the most emphatic witnesses to the conversion of West Berlin into a car-oriented city. Since 2010 the Initiative Bundesplatz, one of the largest citizens’ initiatives in the German capital, has campaigned for the revival of the square as a place to spend time, the limiting of traffic and, in the medium term, the shutdown of the tunnel that slices the square in half. Despite verbal assurances, the campaign has achieved only limited success.

We’re all Staying!

Brochure by Kotti Coop e.V., 2019. In the last ten years, rent increases and tenant evictions have led to a broad-based protest movement in inner-city Berlin, mainly in the district of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg. Kotti Coop was founded in 2015 by residents of the Kottbusser Tor neighbourhood, who are pushing for ‘the development of both social rents and the district’. The association is part of a rainbow coalition in the neighbourhood.