Our answer: definitely something different from the mission statement of the 1910 competition. These images refer to the attitude to life in Berlin and Brandenburg and build and expand on it. They give a positive boost to this region’s best attributes. Therefore, our proposal dispenses with detailed plans and replaces these with six strategic narratives that combine to form a grand scheme.

Model

The ‘star-shaped settlement model’ is Berlin’s current urban development plan. Yet, its structure does not do justice to the nature of the agglomeration area. Berlin was never a monocentric city. The surrounding area itself has proper centralities, to which one cannot do justice with the singular star template. We therefore propose the World Island of Berlin-Brandenburg as a new model. The original term coined by Alexander von Humboldt is no longer compatible with polycentric Berlin and the state of Brandenburg, which surrounds it. However, the concept is nonetheless deeply rooted in the region. The World Island is dynamic and makes room for new, even unforeseeable, centralities while strengthening existing centres. The World Island knows mass and emptiness, habitats, constellations, star dust, gravitation, and orbits, phenomena we have translated into Berlin-Brandenburg narratives.

100% City, 100% Countryside

West Berlin was long a major city without a hinterland. Open space was a scarce and protected commodity. The island location created extremes: high urban density within and emptiness and countryside beyond the border fence. Similar spatial constellations emerged in much of East Berlin as a result of socialist urban planning. Thus, Berlin and Brandenburg today have a unique relationship, which is a key quality of the region. It is not characterised by an endless suburban zone. This is where extraordinary extremes come together: 100 percent city here – high density, urban flair, and spaces dominated by people – and 100 percent countryside there – low density, nature, and rural areas.

Our suggestion: Unconsciously, the World Island has created a development strategy characterised by one hundred percent city and one hundred percent countryside. This dual nature allows it to ideally respond to future challenges ranging from climate change and energy transition to the preservation of natural habitats. It should not only be applied to the borders of the individual settlement centres, but also to the inner peripheries. Large open spaces should remain open: parks, fallow land, unused industrial sites, and old railway tracks. Berlin and the towns and villages surrounding it can densify inwards; space is available, it just needs to be used efficiently.

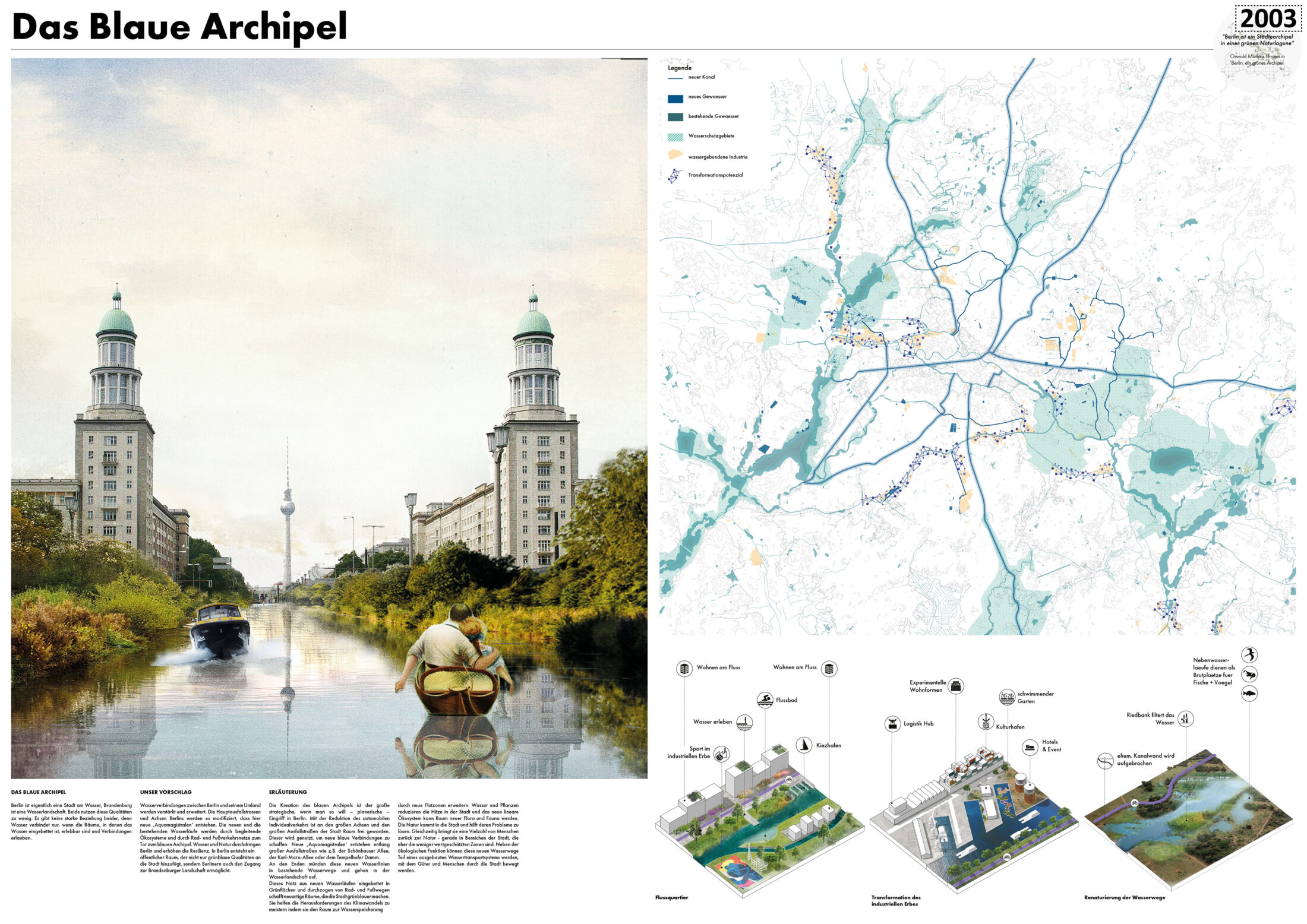

The Blue ArchipelagoBerlin is a city on the water, and Brandenburg is a water landscape. Both places make too little use of these qualities. There is no strong relationship between the two, because water only connects places and people if the spaces in which the water is embedded can be experienced and permit these connections.

Our suggestion: Strengthen and expand the waterway connections and networks between Berlin and the surrounding area. Berlin’s main arterial roads and axes should be modified to create new waterways. The new and existing waterways become the gateway to the Blue Archipelago through accompanying ecosystems and network of footpaths and bike paths. Water and the natural world punctuate Berlin and increase resilience. A public space is thus created in Berlin and it not only adds green-blue qualities to the city, but also gives Berliners access to the Brandenburg countryside.

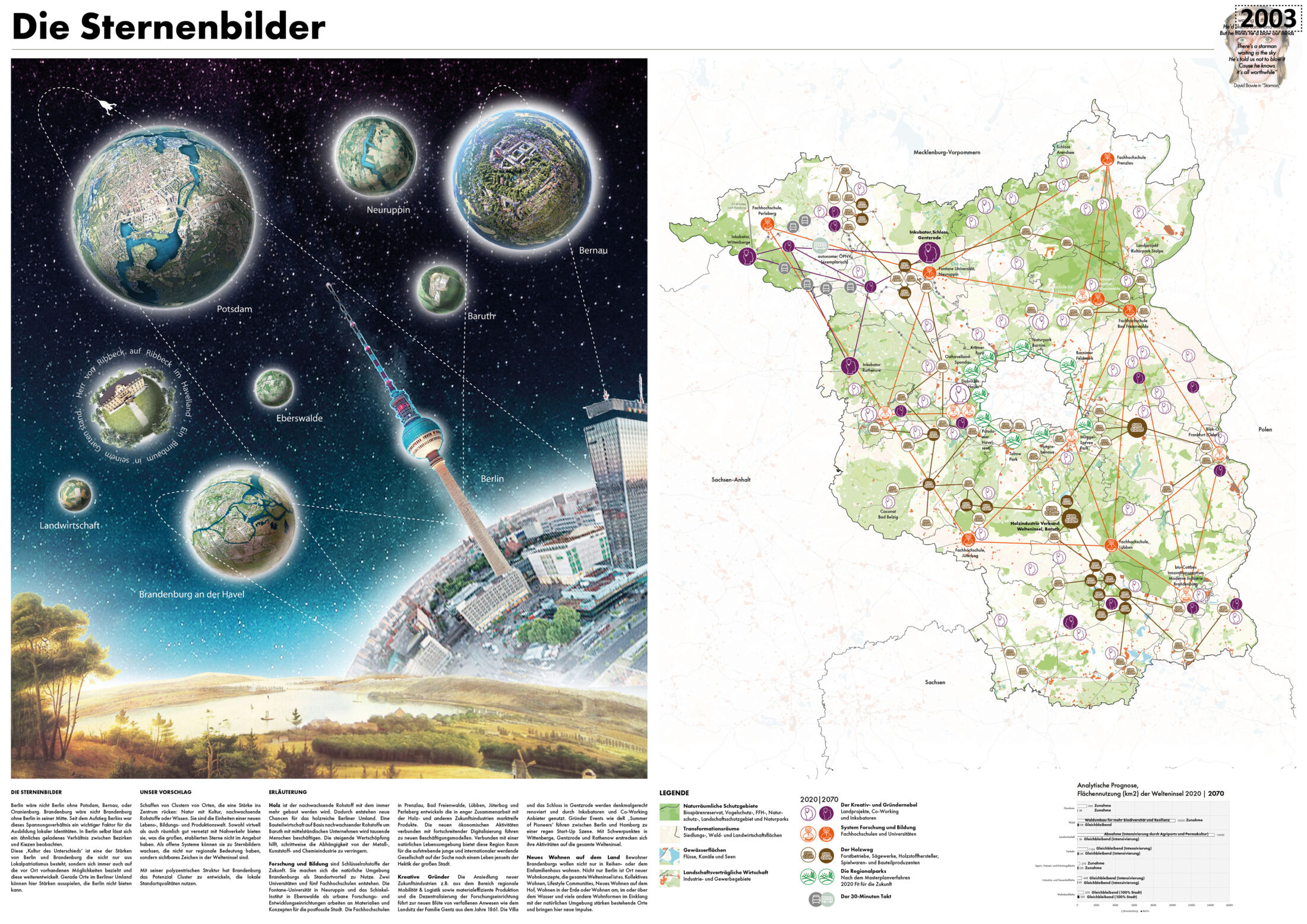

The Constellations

Berlin would not be Berlin without Potsdam, Bernau, and Oranienburg; and Brandenburg would not be Brandenburg without Berlin in its midst. Since the rise of Berlin as a metropolis, this tension has defined local identities. A similarly tense relationship between districts and neighbourhoods can also be observed in Berlin itself. This ‘culture of differences’ is a positive quality of both Berlin and Brandenburg; it is characterised not only by local loyalties, but also by existing opportunities and their further development. Areas directly surrounding Berlin in particular can provide benefits to supplement Berlin.

Our suggestion: Create clusters that focus on these strengths: nature and culture, renewable raw materials and know-how. They are the elements of a new world of habitation, education, and production. Virtually and physically well-connected to regional transport paths, they offer what the larger, more established ‘star’ cannot. As open systems, they can develop into constellations of regional importance and serve as visible symbols of the World Island.

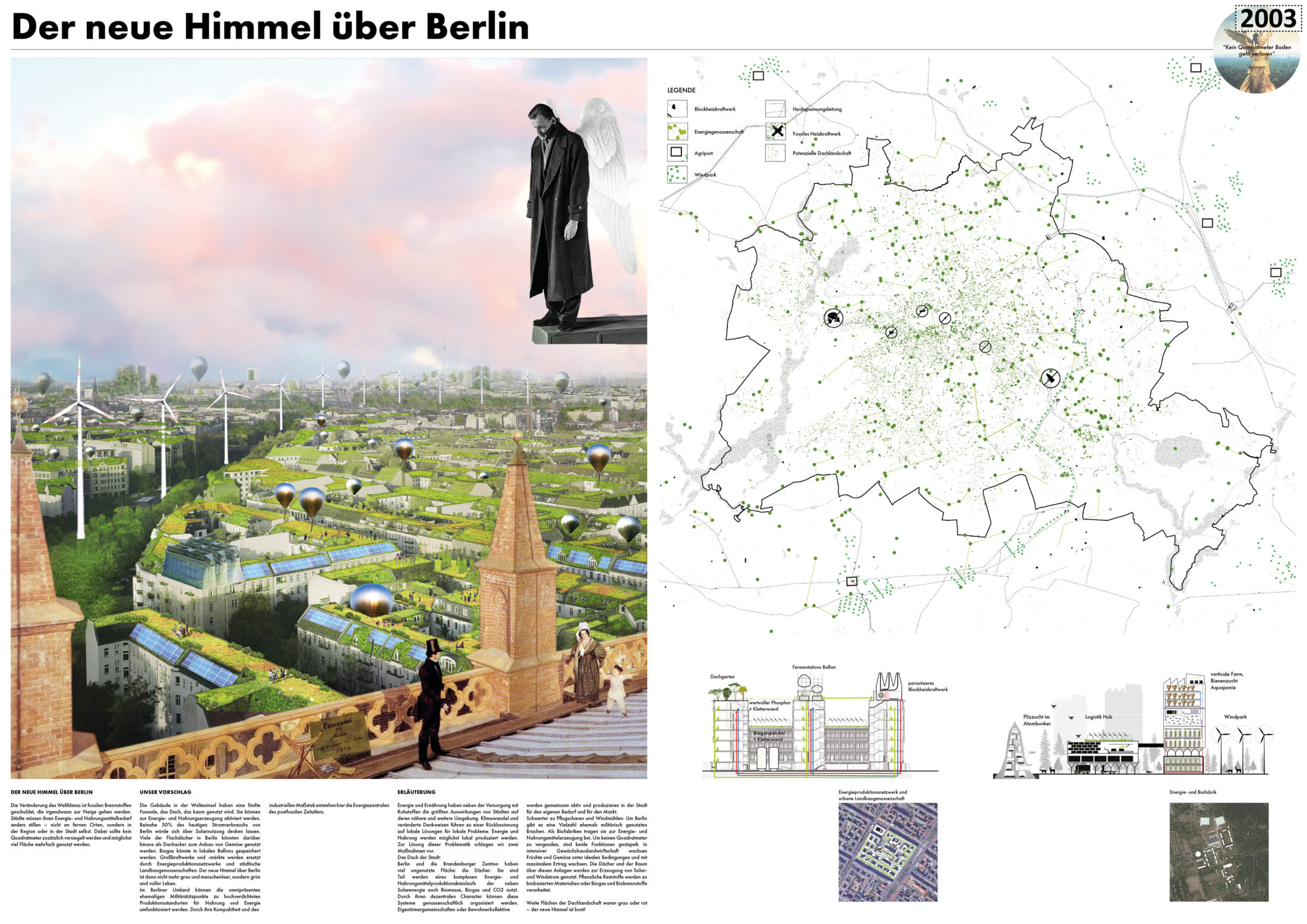

The New Sky over Berlin

Global climate change is largely caused by our consumption and use of fossil fuels, which will eventually run out. Cities must meet their energy and foodstuff needs differently, and not in distant places, but locally, in Brandenburg or even Berlin. No additional square metre should be paved over for this and as much open space as possible should have multiple uses.

Our suggestion: Most of the buildings in the World Island consist of one-fifth façade and a roof that is barely used. These roofs can be activated for energy and food production. Almost half of Berlin’s current electricity need could be generated by solar energy. Many of the flat roofs in Berlin could also be used as roof gardens for growing vegetables. Biogas could be stored in local storage balloons. Large power plants and supermarkets are being replaced by energy production networks and urban agricultural cooperatives. The new sky over Berlin would no longer be grey and barren, but green and verdant. In the areas around Berlin, the omnipresent former military bases can be converted into high-density production locations for food and energy. Their density and industrial scale could help them become ideal energy complexes of the post-fossil-fuel age.

As the city that is always becoming and never is, Berlin will never be truly finished. That is why Brandenburg will never be finished, either: it cannot be. This is true of the place itself and of its residents. They want to be heard and to have a say, to make a difference. They want to shape their city and their countryside. Everyone in Berlin and Brandenburg belongs to a ‘kiez’ (neighbourhood) and embodies that ‘kiez’ in some way. Thus, residents can play a more important, even decisive role in urban and regional development.

Our suggestion: The city and the region should be divided into macro and micro zones. The macro zones consist of essential features: large natural areas, main road networks, local transport, supply networks (unless they can be decentralised), and strategic industrial areas. The micro zones are the areas, neighbourhoods, villages. Local and regional governments are responsible for planning and maintaining the macro zones. The micro zones are governed by their residents with the help of a professional administration. The internet, cellular networks, and other modern technologies are used to involve all residents in the decision-making process. When neighbourhoods are autonomous, there is competition between the them, and their residents define their identity themselves: green, quiet, urban, business-friendly, or more socially inclined.

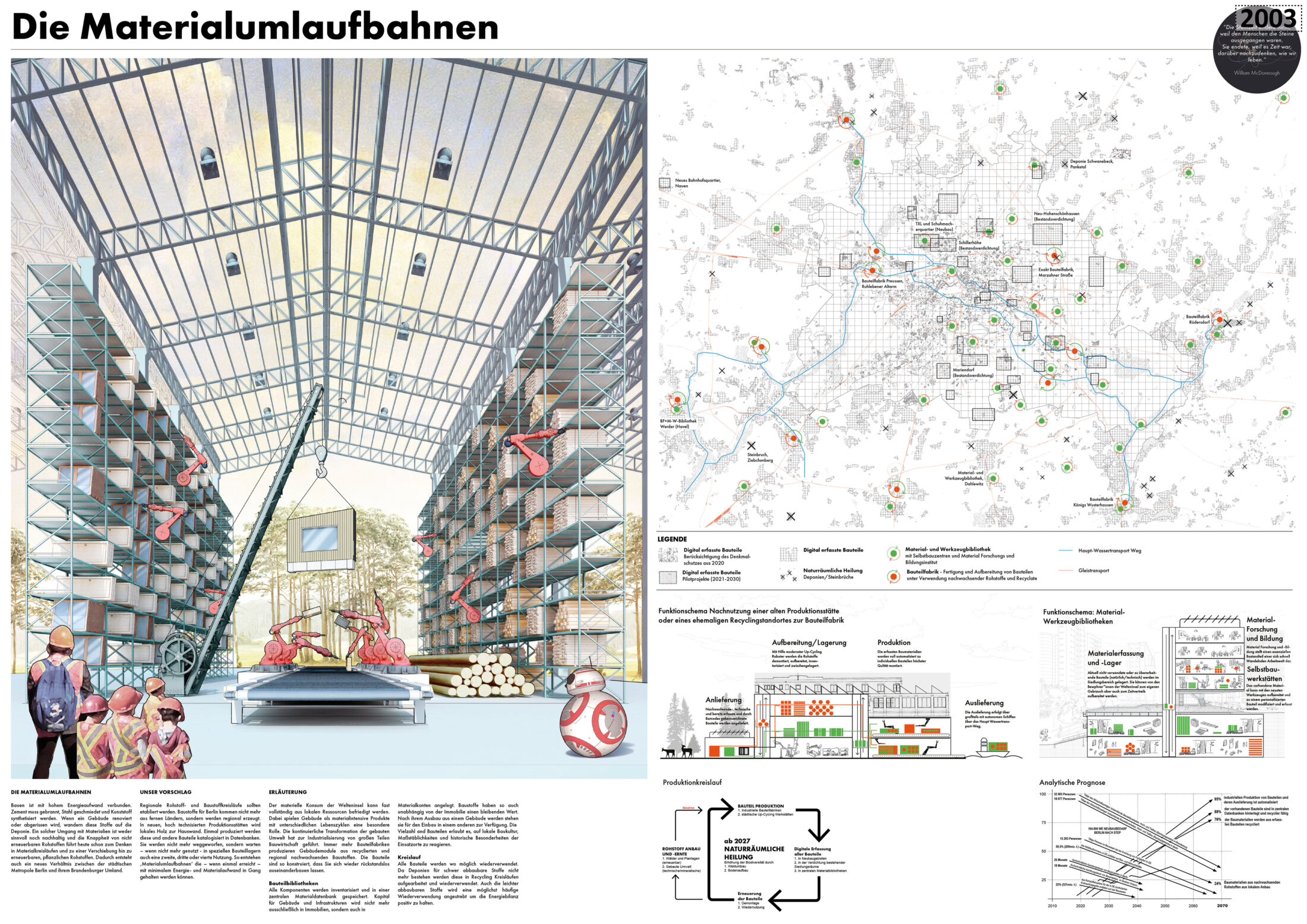

A colourful portrait of different gravitational zones for urban human coexistence in the World Island can emerge from the city of neighbourhoods and the countryside of villages and small towns. Construction-material cycles are associated with high energy consumption. Cement must be mixed, steel forged, and plastics synthesised. When a building is renovated or demolished, these materials migrate to landfill. Handling materials this way is neither sensible nor sustainable, and the scarcity of non-renewable raw materials already leads to thinking in material cycles and a shift towards renewable, and organic, raw materials. This also builds a new relationship between the urban metropolis of Berlin and its neighbouring Brandenburg.

Our suggestion: Establish regional raw-material cycles. Building materials for Berlin should no longer come from foreign lands but be produced regionally. In new, high-tech production facilities, local wood can become a house wall. Once produced, these and other components are catalogued in databases. They are no longer discarded; when they are not in use anymore, they can be stored until they can be implemented in another process, perhaps even more than once. This creates ‘material orbits’ which can continue to function with minimal energy and material expenditure once they are established.